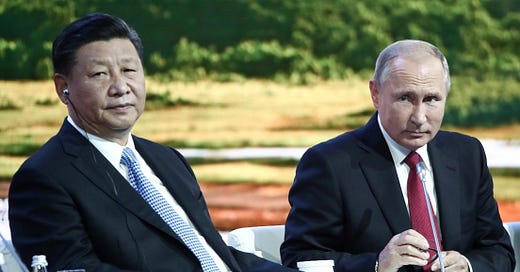

The quasi-alliance between China and Russia has rightly been gathering much attention as the backdrop to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But scant attention has been paid internationally to another important strategic shift – that of the move of South Korea’s new president to strengthen cooperation with Washington and perhaps to join the Quad, currently composed of the United States, India, Japan, and Australia in facing up to China’s goals of hegemony in the western Pacific region.

Whilst not directly related to the Russia-China entente, the Korean move underlines the indirect consequences beginning to flow from China’s moves to confront the US and its allies. China could potentially gain in several ways from its Russian deal and its ambiguous but pro-Russian response to the Ukraine invasion.

First, the West is distracted from Asian issues to which it had been intending to give more focus. Secondly, it makes Russia more reliant on China now that so many economic links with the EU have been broken and are unlikely to be fully restored even if the war ends soon. Thirdly, the US use of the dollar-based financial system to punish Russia will lead to a gradual diversification of currency reserves away from the dollar and toward the yuan and others.

However, several negatives for China are already apparent. Although many countries have reasons not to condemn the Ukraine invasion, only in China (and a couple of similarly absolutist countries) have the facts of invasion of a small country by a huge neighbor not been reported as an invasion accompanied by massive loss of civilian life. It is equally obvious, not just to diplomats, that China’s much-trumpeted commitment to territorial integrity is at odds with its continuing support for Russia’s invasion of a country with which Beijing claimed to have friendly relations.

Internationally, blame for the costs to the global economy and poor countries importing food and fuel, in particular, will not be equally shared between Russia (backed by China) which began the war, and Ukraine’s western allies. Inflation everywhere will undermine several regimes (starting with Sri Lanka) and have unpredictable political consequences.

South Korea has its own concerns about both China and Russia thanks to their perceived unwillingness to rein in North Korea’s ever more ambitious missile and nuclear capacity, as well as Beijing’s bullying trade tactics. The apparent failure of outgoing President Moon’s attempts to initiate dialogue with the North has shifted South Korean attitudes to China, and perhaps also to mending ties with Japan long strained by island and history issues. Given its existing alliance with the US, joining the current Quad might make little actual difference to power balances, but it would be important symbolically.

The Quad is a loose relationship, not a NATO-style alliance. Nonetheless, that gives it a flexibility that enables, for example, India to disagree with the US over the response to the Ukraine tragedy without distracting either from the bigger, Asian, focus. Indeed, had Putin and Xi not embraced so publicly just before the invasion, the US might have been distracted from Asia. In the event the war may have redoubled its efforts to build Asian allies.

The invasion has probably benefited Taiwan, not the mainland, in three ways. First, by drawing attention to some similarities between Russia’s claim on Ukraine (all or part) and Beijing’s on Taiwan. Second, by making supply of weapons to Taiwan less of an issue than in the past as others seek to counter China’s relationship with Russia. Third, by the way that Ukrainian resistance to attack across a land border shows the even greater difficulty that China would face with a seaborne invasion across 160 km of open water. Missiles, unless nuclear-tipped, are not a substitute for boots on the ground who are willing to be killed for the fatherland.

Where all that leaves the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations is not clear. ASEAN itself is too divided to have any influence as a group. China’s economic pull remains very strong but Japan and Korea and other economic players are here too, seeking to profit on breaking supply chains. The Philippines’ tilt to China may shift again after the election, even assuming Ferdinand Marcos Jr wins. Vietnam will remain a staunch opponent of China so long as Beijing pursues its sea claims, Indonesia will gradually increase its sea defenses and cooperation with India. However, meanwhile, a western boycott of its G20 Summit in Bali presided over by Indonesian President Joko Widodo, because of Putin’s assumed presence, would hurt Indonesian pride and provide further illustration of the inability of the US and Australia to treat the country with the respect it deserves.

Western assumptions that Asian countries should engage directly more in Ukraine than, say, the Ethiopia/Eritrea conflict are unproductive. Likewise exaggeration, such as Biden’s claims of Russian genocide. Cold-blooded killing of civilians by an undisciplined military is deplorable but a long way from genocide, and fantasies such as a war crimes trial for Putin.

Xi Jinping’s efforts to show China as representing Asia against the west find little response even among those most economically reliant on China. As for Russia, the Putin era has seen it fall back increasingly on identification with the Russian language and the Russian Orthodox Church as the basis of nationalism, despite the fact that about 25 percent of the population are non-Russian with perhaps 20 percent Turkic-speaking and other Muslims and Buddhists in the North Caucasus, along the middle Volga and the borders with Mongolia, China, and Korea (North). It has long been known that these ethnic minorities have been over-represented in the Russian army and have probably suffered most from the Ukraine invasion.

The Soviet Union tried hard to present itself as a multi-ethnic enterprise creating various levels of separate status within the Union. The Russian Federation today retains much of that official structure but is at odds with the specifically Russian language and Orthodox Christian focus of nationalism. This is not to suggest that Putin, the old KGB operative from St Petersburg, is a Christian believer. But the church is integral to his nationalist appeal and the ideas that Ukraine has always been part of Russia.

It is true that the “Rus” state was initially focused on Kyiv. But that was more than 1,000 years ago and in particular, before the Mongol domination from which permanently changed the political map and eventually led to Moscow’s emergence as the dominant Russian state. Even Moscow as the capital was to be superseded when in 1703 the tsar Peter the Great enlarged his territory to the west and captured a Swedish fort named Nyenskans and proceeded to build a western European-facing and designed city which he named for himself as the capital, St Petersburg.

Russia’s cultural links to western Europe from that period and even during the Soviet era were illustrated by its music, ballet, literature, and indeed to its dominant role in the 1917 revolution when Lenin returned in secret from exile in Switzerland. It remained Russia’s capital until 1918 when fear of German invasion caused Lenin to move it to Moscow. Lenin wanted the new Communist state to be called the Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia.

It is no coincidence that Putin is from St Petersburg, on the northwestern fringe of a huge country, merely 100 kilometers from its borders with Finland and Estonia. Remote from Asian issues but obsessed both with past French and German invasions and with restoring at least the Slav and Christian parts of the old Tsarist/Soviet empire, Putin is trying to cement a heroic place in Russian history. He still might be a winner, but whatever happens to him the world – including China – is the loser from his vanities.