The Belt and Road Turns Into a ‘Debt Trap’ for Beijing

Xi Jinping’s plan to provide infrastructure to the world backfires

By: Salman Rafi Sheikh

With dozens of the member countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) club pushing to renegotiate their loans from China, the BRI is rightly said to have become a project of debt collection rather than one characterized by Beijing’s ‘win-win’ formula of mutual development. With China’s money virtually stuck – and even deeply buried – and its banks facing global pressure to renegotiate and/or provide additional financial help, it seems the trillion-dollar program is entering a self-defeating phase.

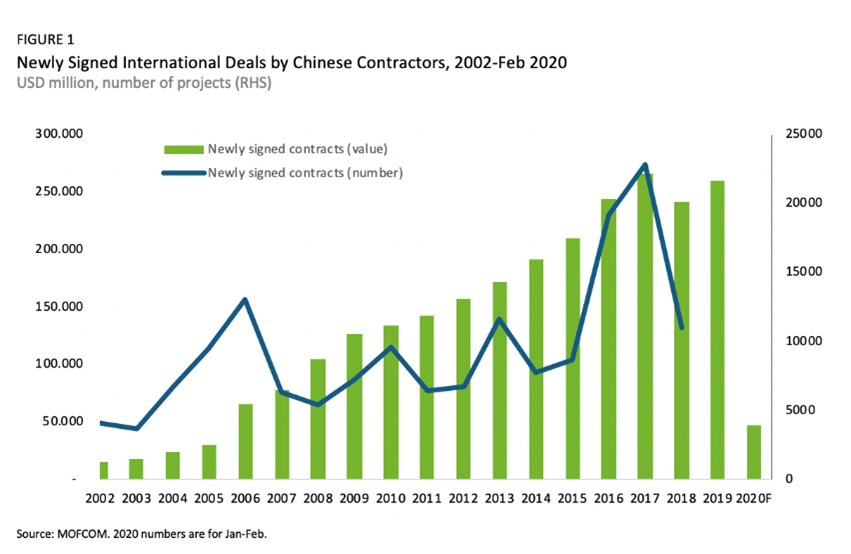

As the year-on data compiled by the US-based Rhodium Group shows, the pace of renegotiating, or even writing off, debt has increased sharply. Between 2017 and 2019, China renegotiated and/or wrote off loans worth US$17 billion. Between 2020 and March 2023, China renegotiated and/or wrote off loans worth US$78.5 billion – money otherwise invested in signature projects such as roads, railways, ports, airports, etc. China has also sharply cut the pace of funding BRI projects, especially as the Covid-19 Coronavirus crisis has bit into global economic growth.

This policy of renegotiation and/or writing off loans is in addition to the newish policy of doling out so-called ‘rescue loans’ to help the BRI recipients avoid sovereign default. In the past two months or so, China has extended this ‘help’ to Pakistan twice, providing over US$4 billion. Pakistan is where the flagship China-Pakistan Economic Corridor was initiated in 2013 but so far has failed to yield any positive results for the host cash-strapped country now facing a potential default.

According to data compiled by AidData, a research institute at the Virginia-based William & Mary University, between 2000 and 2021, China did a total of “128 separate rescue lending operations” spread across 22 countries, including Argentina, Ecuador, Suriname, and Venezuela in Latin America; Angola, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania and Kenya in Africa; Turkey, Oman, and Egypt in the Middle East; and Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Mongolia and Laos in Asia. The total amount spent stood at a whopping US$240 billion.

While China’s purpose is to make sure that the BRI members continue to service their projects, the Sri Lankan case shows that Beijing doesn’t always find success. Since Sri Lanka’s sovereign default more than a year ago, the country has been struggling to find money, with the International Monetary Fund finally coming to its rescue earlier this year when it extended a US$3 billion lifeline.

Zambia, which owed more than US$6 billion to China before its sovereign default in 2020, had its loans canceled six times by China. Yet, the strategy failed to prevent a default. This is despite the fact that Zambia hosts the second-largest number (after Angola) of Chinese construction firms that work on and operate China’s loan-financed projects. Moreover, Zambia has agreed to lines of credit with at least 18 distinct Chinese lenders. But access to these lenders is far from a blessing. Instead, it is making it very complex for the host country and the lenders to coordinate projects and debt repayments. In other words, access to loans is far from a solution. Hence, the default.

Ethiopia is another African state currently in talks with China for a “rescue operation.” The story of Ethiopia is one of the excessive loans taken over the years ultimately proving futile to bring around economic progress. Between 2009 and 2019, Ethiopia borrowed more than US$13 billion from Chinese lenders. Yet, instead of seeing its situation improve, the Ethiopian government is once again pursuing Beijing for help.

The situation is failing to change in most of these countries – Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Zambia, Ethiopia, etc. – primarily because most of these renegotiated loans are being used not for servicing the projects but for providing basic necessities i.e., electricity and fuel and paying salaries to government employees to avoid a sovereign default. A sovereign default is bad for China as well, as it contributes to framing China as a key reason for the situation. But countries remain in trouble, as incurring more and more loans means divesting more and more revenue towards debt servicing.

Pakistan owes more than one-third of its total external debt to China. In the fiscal year 2022-23, external debt servicing accounted for 56.4 percent of total tax revenue. The actual amount, however, has increased sharply due to the rupee devaluation – something that two loan rollovers since the start of 2023 have failed to prevent. Angola, another interesting case that owes more than 40 percent of its total external loans (US$73 billion) to China, is spending about 70 percent of its revenue on debt servicing.

These countries’ economic situation is further compromised by the fact that many of the projects financed by Chinese loans aren’t yielding enough revenue. Whether it is the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka or the strategic port of Gwadar, or even the entire CPEC in Pakistan, or whether it is Uganda, learning perhaps from the failure of the Chinese-funded SRG project in Kenya, unplugging from the China railway project and turning towards other countries to connect with neighboring Kenya, there is a growing realization that partnership with China doesn’t mean an automatic transition to profit and development. In fact, 128 rescue operations show that profit and development are far from possible.

This realization not only means a potential shift in many countries away from China but also for the BRI countries to shift towards other countries. Uganda turned towards Turkey, which has thus far invested more than US$70 billion in the African continent.

Many studies have found that while building infrastructure has meant incalculable help to bring some impoverished countries into the 21st century, the payback, both for China and the recipient countries has been far less than anticipated. With Chinese projects not working and with China finding it crucial to keep inflating these countries with loans – including “rescue loans” – many other countries, including western ones, are stepping in.

So far, it is the IMF that seems to be becoming a replacement for China. Between 2020 and 2022, IMF loans for Sub-Saharan Africa saw a substantial increase. The Fund provided more than US$50 billion, which is more than twice the amount provided in a decade since 1990. The fact that this increase parallels BRI going out of steam means that there is opportunity for China’s global economic rivals to fill the vacuum with a development plan of their own.