By: Viswa Nathan

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is in a bind, facing pressure on two critical fronts – his administration’s expanding alliance with the United States, and the need to observe international rules for attracting foreign investment. On both fronts, his predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte who completed his six-year term with nearly 70 percent approval rating, looms large while the forces that helped Marcos win a landslide victory in the 2022 presidential election are beginning to feel uneasy over fundamental differences in policy and strategy.

An Inherited Liability

Ironically, neither of these problems is of Marcos’s making, notes a Marcos aficionado. “He inherited them from his predecessors and is now left with only unpalatable options.”

The present crisis, the source points out, stemmed from China’s claim over almost the entire South China Sea. But for it, former President Benigno Aquino III would not have yielded to Washington’s pressure to seek UN arbitration over China’s sovereignty claims, and later would have signed with Washington, Manila’s defense partner, a new military pact called the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), thereby granting the US five Philippine military establishments for stationing US soldiers and weapons, in addition to renaming its territorial waters the West Philippine Sea.

Duterte, who succeeded Aquino, disregarded that agreement as he pivoted away from the US to embrace China. But it didn’t help Manila in protecting the nation’s territorial integrity, or even economically. In the following years, China, taking advantage of Duterte’s rift with Washington, became increasingly assertive in making territorial claims based on its self-proclaimed nine-dash line and preventing Filipino fishermen from fishing even in internationally-recognized Philippine waters.

Assuming office in such circumstances, Marcos, says the observer, had to take a stand. So he drew his line in his inaugural statement to the nation: “I will not preside over any process that will abandon even one square inch of territory of the Republic of the Philippines to any foreign power.”

Then, faced with the reality that his nation of 7,100-plus islands has no air force or navy capable of protecting its borders, he had no alternative but to turn to the old ally; or, say, give in to the persuasions of the old ally. He granted four additional military bases for the US to expand its military presence on Philippine soil.

Marcos’s action has made an impact on public opinion. EDCA, by definition, was for the defense of the Philippines against any external threat and natural calamities like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, typhoons, etc. But in the changing geopolitical situation, many Filipinos now see the nine locations across the country with US soldiers and weapons as America’s assault stations to defend Taiwan against a potential Chinese military takeover. The Philippines thus becomes a target for Chinese attack.

“Do we want to die for Taiwan?” asked a political commentator while Duterte, interviewed by the television evangelist, Pastor Apollo Quiboloy early March, said that the Philippines is now a platform for America to fight for China’s renegade island province. Stressing that he wasn’t criticizing Marcos, Duterte said: “If that’s your decision, Mr. President, we will just follow…But at whose national interest? Definitely not ours.” China, said Duterte, “is not our enemy.”

Nonetheless, despite all the saber-rattling, fearmongering, and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s desire to make integrating Taiwan with China his crowning glory, the possibility of a war over Taiwan is remote for many reasons.

Beijing has spent considerable resources to analyze the collapse of the Soviet Union and learn from it. It is now learning new lessons from Russia’s Ukraine adventure. It is also uncertain how the population would react to the unpredictable consequences of a war with Taiwan, as they have grown restive in Beijing, Shanghai, and many other cities against the country’s Covid-19 lockdown, calling for Xi and the communist party to stand down.

Human Rights

Meanwhile, Marcos’s attempt to promote foreign trade and make the Philippines a preferred foreign investment destination demands a tactful strategy. Many might see the European Union’s human rights conditions for economic relations, and the International Criminal Court’s attempt to investigate the drug war killings under Duterte, as the president and previous mayor of Davao are one and the same issue. But Marcos wants them treated separately, and to judge him, as he appealed to the world nearly a year ago, by his actions rather than by the actions of his forebears.

Apparently, he is receiving sympathetic ears. A European legislators delegation visiting Manila in late February acknowledged that human rights situation is better under Marcos than under the Duterte regime, and the EU has since extended its certification of Filipino seafarers despite Manila’s standoff against the International Criminal Court (ICC) on the question of investigating Duterte’s alleged human rights violations.

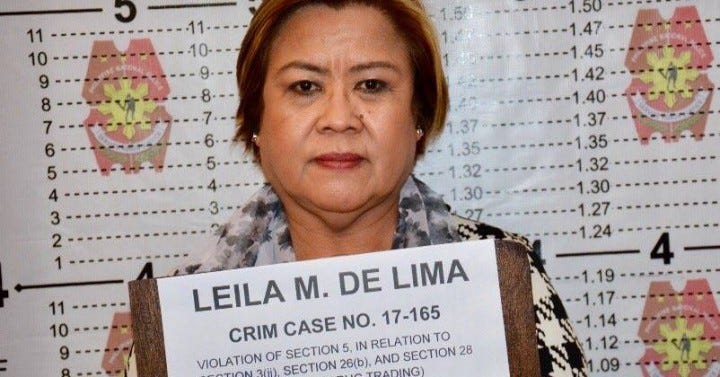

However, high-ranking EU leaders maintain that the continued detention of Duterte’s prisoner, the former justice secretary and later senator, Leila de Lima, remains a bone of contention on which Manila could lose the GSP Plus tax exemption its exports to the EU market now enjoy. Releasing De Lima and returning to the ICC would be a clear sign in which direction the country wants to move, which is “absolutely in line with what we expect from GSP Plus partner countries,” said Hannah Neumann, who led an EU delegation to the Philippines early this year. The European Parliament, she said, has been clear that whoever wants to have preferential access needs to uphold social standards, human rights standards, environmental standards. “This is not going to go away.”

Last month, the EU special representative Eamon Gilmore, visiting Manila, called on De Lima in the prison and later called for her release “without further delay.” A posting on the Facebook page of EU representation in the Philippines also spoke of the EU’s continuing concern over her detention.

Marcos’s justice secretary, Jesus Crispin Remulla has said if De Lima’s camp filed a habeas corpus petition, the government would not oppose it. But the indication so far is that the woman who once said she was willing “to be shot in front of Duterte if the drug allegations against her are proven true” would rather see the government, which has no credible witness to move the case to hearing, drop its charges rather than beg for freedom.

The longer the delay, the situation could turn worse for Marcos.