If It’s Built, Cambodian Canal an Economic and Environmental Disaster

China’s Belt and Road Initiative pulls out

By: David Brown

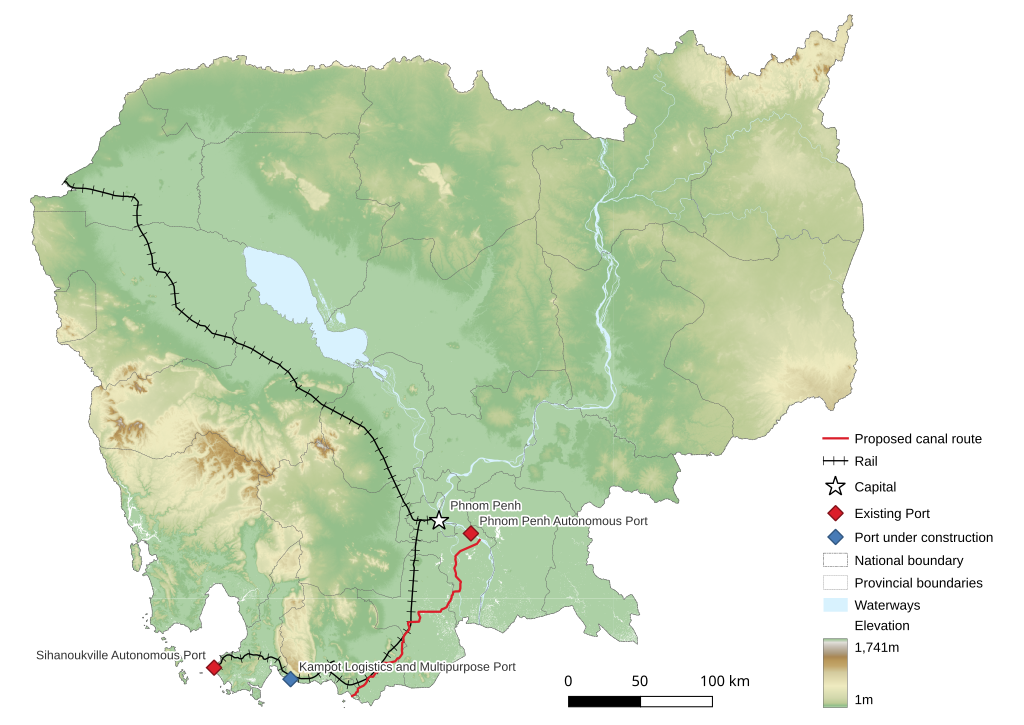

There are good reasons why Cambodia should abandon its plan to build a canal between the nation’s capital, Phnom Penh, and Kampot, a coastal town some 180 km to the southeast. None of them seem likely to change the minds of Hun Sen, Cambodia’s prime minister for 38 years, or his son Hun Manet, installed last August as the new prime minister, or, absent a signal from the top, of the rest of Cambodia’s governing class.

From spring 2023, stories in Khmer media have extolled the ‘Funan Techo’ canal project. References to participation by BRI, China’s Belt and Road Initiative, gave the canal project undeniable credibility because BRI had ably managed the development of the Port of Sihanoukville and the construction of an all-weather four lane highway to the port from Phnom Penh.

Toward the end of 2023, Khmer media referred frequently to an agreement in principle reached between Cambodian leaders and top BRI executives. The public was given to understand that the BRI would line up Chinese companies to dig the canal as a BOT (build/operate/transfer) project. Reports of a high-level meeting at the office of the Council for Development of Cambodia that October inspired confidence that the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) would front the US$1.7 billion said to be needed.

But in fact, sometime early this year, BRI officials had informed Khmer planners of its decision not to finance the canal. After an awkward period of media silence, Prime Minister Hun Manet told Cambodia’s citizens on May 16 that construction work would begin in August, stressing that “an autonomous waterway is needed to maintain Cambodia’s economic and political independence.” The Khmer Times reported that Cambodian entities would be the majority shareholders of the project and reminded possible doubters that 40-plus experts had studied the project for 26 months. And Hun Sen, still wielding power as president of Cambodia’s Senate, reminded citizens that he’d “never made a wrong decision.”

Let’s think about that…

The proposed canal is billed as freeing one-third of Cambodia’s foreign commerce from having to navigate Vietnamese waters. Cargo is to be carried to and from the coast in ships of up to 5,000 deadweight tons and there transshipped to or from the large container or bulk carriers that ply the seas to East Asia or North America.

It’s hardly surprising that Cambodia should want also to build up freight handling and forward shipment capacity at one of its own ports on the Gulf of Siam. However, Cambodia does not need a redundant and environmentally iffy cargo canal

In an analysis just published by Mongabay, environmental engineer Pham Phan Long concludes that the US$1.7 billion cost estimate by the canal approved in mid-May by Cambodia’s Council of Ministers is low by a factor of two or three.

There is no plausible economic argument for digging a canal. Already there’s a BRI-built and managed four lane highway from Phnom Penh to the Port of Sihanoukville and, if that’s not enough, there’s an aged railroad that could be upgraded. In addition, efficient container shipping terminals already exist at Cai Mep and Cat Lai, about 60 km southeast of Ho Chi Minh City and easily reached from Phnom Penh via the two major distributaries of the Mekong River. For cargoes headed for East Asia or North America, both Mekong routes are 50 percent shorter than via the canal that obsesses PM Hun Manet and his father, and either route accommodates 7000 dwt vessels – twice the tonnage of the largest motorized barges projected for the canal.

Vietnam Could Do Better Too

The Vietnamese can and should improve their act. In particular, they ought to help establish a system of bonded goods transport instead of inspecting cargos bound for Phnom Penh virtually item by item. Further, cargo vessels plying the Mekong typically wait long hours for Vietnamese customs authorities to arrive at the border post and OK their passage after what a well-respected Cambodian analyst describes as “complex, time-consuming and costly border-crossing procedures and paperwork.”

And, though there’s a history of intermittent ill-will between Phnom Penh and Hanoi, efficient cross-border goods transit is indeed possible. Khmer and Vietnamese interlocutors ought to study the $5 billion Vung Ang port and rail link project for pointers. This project will link a hub in southern Laos by rail to Lao-owned and managed container terminals on the central Vietnamese coast. It was talked about for a decade. Now it is moving forward briskly.

Meanwhile, instead of engaging Vietnamese counterparts in discussion of upgrading the existing Cai Mep to Phnom Penh shipping link and exploring its joint management, Cambodian reporting on the Funan Techo Canal project is drearily repetitive. None question official pronouncements. They laud the canal’s purported benefits, insist disingenuously that Phnom Penh has met its Mekong Treaty notification obligations, and ridicule reports that the Vietnamese consider the canal to be a possible security problem.

For the Floodplain, Non-Feasibility is Good News

It is the canal project’s true cost of construction and, if built, its uncertain payback and inevitably high user fees that most persuasively explain Chinese investors’ loss of interest. At this point, the Funan Techo Canal seems unlikely to advance much beyond ground-breaking. For the hydrologists and agricultural experts who have warned of the adverse impacts inherent in Cambodia’s canal scheme, so far with little effect, the project’s non-feasibility is good news. It may also ease the worries of Mekong River Commission staff who have attempted since 1995 to hold signatories to their pledge to cooperate in maintaining the natural flow of the Mekong mainstream.

There are two big environmental worries. Cambodians aside, experts seem unanimous that dry-season diversions of water into the canal will induce further intrusion of salt water into the Mekong’s delta distributaries. Also, Le Anh Tuan of Can Tho University and Brian Eyler of the Washington, DC-based Stimson Center have warned that without major adjustments in the canal’s design, it would act as a huge levee, bisecting a million-hectare transboundary floodplain that stretches south and east from Cambodia deep into Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. In its current state, Eyler explains, the floodplain is a hugely productive zone for agricultural production and fisheries, but as planned, “the canal will disconnect the floodplain, creating a dry zone to its south and a wetter zone to the north. “

So far, the Phnom Penh authorities have ducked Cambodia’s obligation to discuss the likely impacts of the canal project on the Mekong River with fellow members of the Mekong River Committee, disingenuously insisting that the project affects only a ‘tributary’ of the Mekong, and that Cambodia has provided, in an August 2023 notification to MRC staff, all the information that fellow signatories to the Mekong River Agreement require.

Note: In researching this article, the author worked closely with Pham Phan Long, an American environmental engineer. Readers wishing greater detail on Mekong Delta hydraulics and on the relative costs of shipping cargos from Phnom Penh via the projected canal instead of via the Mekong River will find it in Mr. Long’s July analysis for the online environmental journal Mongabay.