A Hong Kong Judge Changes His Spots

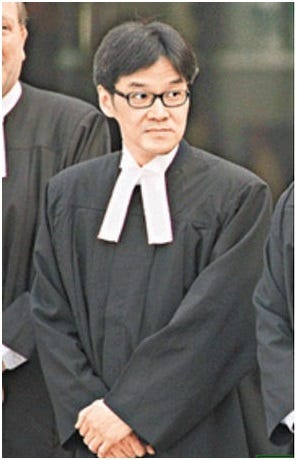

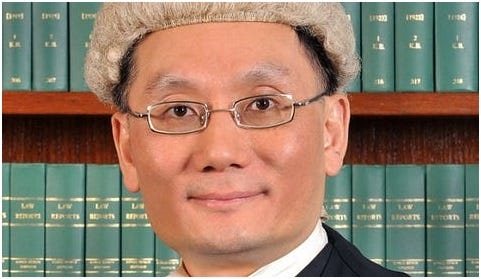

Kwok Wai-Kin has transformed from an unassuming civil servant to a virulently pro-Beijing national security judge

By: Samuel Bickett

The following, though much longer than Asia Sentinel’s normal articles, is reprinted with permission from the “Hong Kong Law & Policy” blog on Substack of Samuel Bickett, formerly an American corporate lawyer who was arrested in 2019 for allegedly interfering with a police officer who refused to identify himself and who was beating a youth who reportedly had jumped a turnstile. Bickett was ultimately sentenced to four months and two weeks in jail. The experience turned him into a human rights lawyer. He is now based in Washington, DC as a legal fellow at the Georgetown Center for Asian Law.

Since early January, many Hongkongers have been captivated by the ongoing testimony of former Stand News Editor-in-Chief Chung Pui-Kuen, who is being prosecuted for sedition alongside former chief editor Patrick Lam and their now-defunct company. In a city where anti-establishment speech is heavily suppressed, Chung’s eloquent defense of the free press has garnered public praise and exposed the prosecutor questioning him, Laura Ng, as inept.

Yet throughout Chung’s testimony, the prosecution has violated the defendants' rights by producing, day-after-day, hundreds of documents that it never gave to the defense—a violation of law and the Prosecution Code which, in egregious cases, warrants halting the proceedings permanently. But each time Ng has revealed another set of unproduced materials, the judge in the case, Kwok Wai-Kin, has quickly dismissed objections from defense counsel. Over and over, he has not only ordered the trial to proceed, but even allowed the withheld documents to be used to cross-examine Chung.

To those unfamiliar with Judge Kwok, his actions might seem shocking. But to court watchers, his actions aren’t surprising at all.

Since the 2019 Hong Kong protests, Judge Kwok has become notorious for his controversial rulings and political biases. Even in a judiciary increasingly influenced by Beijing, Kwok stands out. In 2020, Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma suspended Kwok from hearing political cases after he praised a defendant who stabbed three peaceful protesters and compared the victims to terrorists.

The next year, however, newly appointed Chief Justice Andrew Cheung reinstated Kwok, paving the way for his appointment as a national security judge. As a result, Kwok now handles one of the heaviest caseloads of high-profile, politically charged "national security" cases in which the proceedings are choreographed and conviction is inevitable.

Judge Kwok has become one of the most controversial and influential figures in Hong Kong’s judiciary. This will trace Kwok’s journey from ordinary civil servant to pro-Beijing radical, and his comeback from disgrace after the stabbing case to a prominent national security judge.

Judge Kwok is an example of how Hong Kong’s judicial system, once respected for its independence and professionalism, has been eroded by Beijing’s interference and intimidation. Kwok’s radical views and actions have not hindered his career, but rather boosted it, as he has become a loyal enforcer of the Chinese regime’s crackdown on dissent and autonomy in Hong Kong. By examining Kwok’s biography and verdicts, we can gain insights into how and why many judges and magistrates in Hong Kong have abandoned their legal principles and ethics, and succumbed to the pressures of nationalism, ambition, and fear. Through Judge Kwok, we can witness the transformation of the judiciary from a guardian of the rule of law to a tool of political oppression.

An ordinary civil servant

On May 23, 1989, as pro-democracy demonstrators occupied Tiananmen Square in Beijing, a group of Hong Kong lawyers published a statement of solidarity. In the document, they declared that they “support the student movement, oppose martial law, oppose the military, oppose violent suppression, oppose a news blackout, and call for open and forthright dialogue towards a peaceful solution.”

One of the signatories to this principled defense of democratic rights was a young barrister named Kwok Wai-Kin. Kwok was born and raised in Hong Kong, receiving his law certificate in 1982 after studying at the University of Hong Kong. He was a product of a British legal education system and society that, despite its many flaws and failures during the colonial period, by this point was teaching its lawyers to value rule of law and individual rights. So it was unsurprising that Kwok would support the young men and women demonstrating for just this sort of justice and fairness across the border in China.

In 1992, he was appointed as a magistrate, later becoming a chief magistrate. In his early years, he did little to distinguish himself, steadfastly applying the law without much fuss. In his many non-political rulings, he comes off as a by-the-books type, carefully hewing to sentencing guidelines and legal precedents in a range of cases from drug dealing to burglary. Indeed, one experienced barrister I’ve spoken to for this article described Kwok’s early reputation as that of an unassuming civil servant, and a “nice and fair guy.” Another barrister reported that he was largely unfamiliar with Kwok “until he became infamous” in 2019.

Outside of the courtroom, Kwok’s only brush with notoriety came in a minor 2004 incident in which he was accused in his private capacity of pressuring the Immigration Department to waive a replacement fee for a lost ID card. The Chief Justice at the time dismissed it as a private matter, and no action was taken.

In one of his final cases as Chief Magistrate before promotion to the District Court in 2012, Kwok demonstrated his commitment to the law, as well as a bit of an independent streak. The defendant in the case was accused of “accessing a computer with a view to dishonest gain” by using a smartphone to secretly film women in a bathroom. In court, the defendant wanted to plead guilty, but Kwok rejected the guilty plea because he had concerns that the prosecution was overstepping by characterizing a smartphone as a computer—an exceedingly unusual move by a judge where a represented defendant pleads guilty. After a trial, Kwok found the defendant not guilty.

The verdict was overturned on appeal, but at a time when the judiciary was still believed to be positioning itself as independent of the government and Beijing, the case helped establish Kwok as a defender of that independence. One barrister I spoke to believed it was this case more than any other that allowed Kwok to break out of the “career purgatory” of Chief Magistrate and obtain a rare promotion to the district court later the same year.

It is possible that Kwok was simply a dedicated, principled civil servant before something in his life led to a drastic shift in his political views, causing him to become a true believer in the Communist Party and its right to bring the judiciary to heel. In hindsight, however, his actions suggest a less noble explanation, one that is common among Hong Kong’s government officials: that as Hong Kong changed, many of its civil servants sought to further their own careers by changing with it

In 1989 as a young lawyer, Kwok’s career advancement in British Hong Kong depended on supporting the Tiananmen protesters, so that’s what he did. In 2012, during the peak days of the post-Handover independent judiciary, his career advancement depended on showing his independence from the government, so he issued decisions showing his independence. Then sometime during or after the 2014 Occupy Central protests, as Beijing began encroaching on political dissent and stoking nationalism, he realized that his career advancement depended on pleasing Beijing, so he changed direction once again.

Canary in the coal mine?

The first indication that Kwok’s views on politics and law might have begun turning more extreme was in 2018, in the period of political uncertainty between the 2014 Umbrella Movement and the 2019 democracy protests. Kwok was one of several District Court judges assigned to rioting cases stemming from the 2016 “Fishball Revolution.” In that incident, during a traditional celebration in Mongkok commercial district over Chinese New Year in which vendors would hawk traditional snacks, Food and Environmental Hygiene Department officials arrived at the scene and began checking hawkers for cooked food licenses, which many did not have.

The tradition of hawkers selling snacks at Chinese New Year had a long, well-established history, so the efforts to end the practice drew anger from members of the public already resentful of perceived overreach by the Beijing-friendly government. In response, “localist” leaders—a moniker given to those who supported the Hong Kong self-determination movement—sent out calls on social media for supporters to come defend the hawkers.

Police in riot gear then arrived and moved to shut down the event, leading to violent clashes. The police dubbed the entire event a riot and arrested dozens, many of whom were merely present and had nothing to do with the violence.

The alleged rioters were charged in groups, with Kwok overseeing a judicial trial for 11 of the defendants. Kwok convicted all 11, despite little evidence that most of them had been violent. But while his reasoning showed a clear shift towards punishing Beijing’s opponents, he still hedged his views throughout. While maintaining the convictions was justified, Kwok distinguished himself from the opinions of some of his colleagues—and post-2019 Kwok himself—by maintaining that physical presence at a riot was not enough for conviction. Rather, he wrote:

“The accused must…be physically involved in the riot. Since rioting is an additional act of disrupting social peace in addition to illegal assembly, the defendant must participate in these acts of disrupting social peace to constitute participation in riots. The defendant may participate in the riot in different ways or degrees, but the defendant must do some individual activity in order to promote the occurrence and/or conduct of the riot (“some individual activity in furtherance of the riot.”

In other words, while Kwok took the position that no violence was needed, some action in furtherance of riot was; as such, he rejected the government’s contention that mere physical presence was enough for conviction.

Nonetheless, at sentencing, Kwok was harsh, showing little leniency towards the defendants or taking into account the complex social situation and aggressive police response that led to the violence. He rejected counsel arguments that each defendant should only be held responsible for the crimes they took part in, instead concluding that the defendants bore “collective liability” for the riot as a whole.

This finding allowed him to sentence even nonviolent defendants to significant prison terms. His sentencing of an autistic man, Ng Ting-Kai, to two years and four months in prison went against the advice of probation officers. The longest sentence of four years and three months was given to a 17-year-old minor, Mo Jia-tao, while a 73-year-old received three years and five months.

Kwok’s decision, along with several other decisions from his colleagues hearing other rioting cases stemming from the same incident, marked a significant departure from previous rioting cases, where sentences for participants were usually measured in months, not years. Even in the 1960s pro-CCP riots in British-occupied Hong Kong, which caused multiple deaths, defendants convicted of rioting typically spent only a few months in prison. In contrast, the 2016 Mongkok protesters caused little property damage and there were no fatalities, yet the sentences handed down were extraordinarily long.

While Judge Kwok was not the only judge involved in this drastic increase in punishments for political activity, he played an important role in it.

In his reasons for sentencing, Judge Kwok made a statement that would later come back to haunt him. Rejecting defense arguments that he should take into account the political circumstances surrounding the riots, Judge Kwok wrote:

“When sentencing, the court will never consider whether the riots are derived from political beliefs, let alone whether these political beliefs are correct. The court will only consider the level of mass violence and the extent to which social tranquility has been damaged to make the sentence… The court will not join the political debate, nor will it judge the right and wrong of political claims, because these are not the functions of the court.”

Kwok’s handling of the Mongkok riot case drew attention, but still showed a level of restraint. Few imagined how far he would ultimately be willing to go to advance Beijing’s political interests.

A “noble sacrifice:” Judge Kwok expresses sympathy for a man who stabbed protesters

In June 2019, Hong Kong exploded in mass demonstrations involving millions—first in opposition to a law that would have allowed Hongkongers to be extradited to China, and then more broadly for government and police accountability, democracy, and human rights. In the months that followed, more than 10,000 people were arrested and thousands prosecuted, often for nonviolent crimes like unlawful assembly and possession of “weapons” such as laser pointers. In contrast, no police officers and only a tiny handful of those committing violence in support of Beijing were prosecuted.

Judge Kwok was assigned to hear one of these rare cases involving a pro-Beijing defendant. On August 20, 2019, Tony Hung stabbed three democracy supporters who had been adding pro-democracy sticky notes to a “Lennon Wall.”

As Kwok described it in his reasons for sentence, Hung had seen pro-democracy supporters at the site, gone home, grabbed knives, returned to the scene, argued with two women posting to the wall, then stabbed them and another bystander who tried to intervene. All three were hospitalized, with one of the women, a 26-year-old surnamed Wong, left in critical condition due to a collapsed lung.

Hung pled guilty to wounding with intent. On April 26, 2020, Kwok convened the court to deliver his sentence. Even among a public that had by that point become nearly immune to outrages from officials, the words that flowed from Judge Kwok’s mouth shocked the city.

In recounting the verbal exchange between Hung and his victims prior to the stabbing, Judge Kwok said that Hung had blamed Wong for “beating people at the airport”—a reference to a mass sit-in at Hong Kong International Airport a week earlier in which a small portion of protesters became violent. Wong then denied that she or the friend with her, a 35-year-old surnamed Li, had done any such thing: “We didn’t beat anyone,” she replied at the time. But despite the trial having nothing to do with the airport incident, Judge Kwok went out of his way to argue at length that Ms. Wong—a victim in the case—was a liar:

“Ms. Wong’s answer is obviously not true, because on August 6, 2019, shortly before this incident, there was an incident where demonstrators kidnapped and beat a Mainland [China] journalist at Hong Kong International Airport, which was broadcast live on TV. I believe that anyone who supports rule of law would be shocked by the images he saw at that time.

He then excused Hung and blamed Wong’s stabbing instead on protesters who had been mean to Mainland Chinese at the airport:

“I believe that the defendant felt particularly deeply about the attack on the Mainland journalist at the airport, because he works as a tour guide, primarily for tourists from the Mainland. When a large group of people abused and insulted Mainlanders out in the open at the airport, and no one reached out to help, this image must scare Hong Kong visitors, especially those from the Mainland. The defendant must have felt that the airport incident was the ‘nail in the coffin.’”

That was bad enough, but Kwok was just getting started.

He then launched into an extended political tirade. He lumped all protesters together as violently committing “criminal damage” and “wounding” people despite the vast majority of protesters, including the injured victims, demonstrating peacefully. He gave an extended description—without providing evidence—of an unrelated incident in which, Kwok claimed, some protesters surrounded a mall and used violence in an effort to free others who had been arrested. He described the protesters’ actions as “cultural-revolution style extremist acts.” He blamed protesters for “economic depression” and “unease” in society.

He then launched into a lengthy defense of the defendant’s actions and blamed the “demonstrator” victims:

“The defendant obviously knew at the time that people should not be stabbed, but he also could not accept the demonstrators’ behavior of undermining Hong Kong’s economy and societal peace.”

He said that Hung was “an involuntary sacrifice” who “had already been left bloodied and dying by this social movement.”

In perhaps the most shocking statement of all, with the victims and their families looking on, he declared that the demonstrators, by “putting pressure” on others with their protests, were the same as terrorists who murder hostages:

“I believe that if the demonstrators are really pursuing what they claim to be democracy, freedom, human rights, and the rule of law, they should think about it before taking radical actions. Before they hurt their claimed enemies, their actions will only first hurt ordinary people who generally just want to live and work in peace and contentment. If they put pressure on their enemies by harming ordinary civilians, this is no different from killing a hostage if the enemy refuses to submit. This is an out-and-out act of terrorism.”

Wrapping up his speech, Kwok declared that the defendant had “noble sentiments” towards the victims (presumably in contrast to the victims themselves, who, Kwok had already established, were sticky-note-wielding terrorists).

He then reduced the sentence by a full two years from the starting point of six years—an enormous deduction in the context of Hong Kong’s political cases, where deductions are rare and, if given, tend to be measured in weeks or a couple of months at most. Kwok said that it was “unfortunate” that the law would not allow him to reduce the sentence further.

The final sentence was four years, of which the defendant would likely serve a little more than two and a half years—an incredibly light sentence for stabbing three people and nearly killing one.

To illustrate how disproportionate this sentence was, compare it to the rioting sentences handed out to democracy supporters since the 2019 protests. As of this month, according to as-yet unpublished statistics compiled by writer and human rights activist Kong Tsung-Gan, Kwok and other judges have sentenced 261 demonstrators to an average of 3 years and 8 months imprisonment for “rioting” during the 2019 protests, most of them merely for nonviolent participation in political assemblies where other people breached the peace.

The fallout: Chief Justice Ma removes Judge Kwok from political cases

By the time of Kwok’s ruling, the public had grown accustomed to anti-protester bias in the courts. However, Kwok's language was particularly extreme, and the case was one of the few brought against perpetrators of violence against protesters, leading to heightened expectations of justice. As a result, the news struck a nerve among the public, prompting prominent activists such as Joshua Wong and Ventus Lau to voice their outrage and demand justice. The incident received widespread media coverage, including abroad.

Two days later, the Chief District Judge removed Judge Kwok from another protest case assigned to him. A month after that (once the 30-day period of time in which the defendant could appeal had expired) Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma issued a statement on the matter. It was highly critical of Judge Kwok, particularly by the standards of collegiality that are the norm amongst judges:

“Judges and judicial officers must not be biased nor, just as important, be reasonably perceived to be biased for or against any persons or causes. For this reason, they must refrain from unnecessarily expressing in public, including in their judgments, any views on matters that are controversial in society or may come before the courts for adjudication. This is particularly so with political views of whatever nature. Where the resolution of an issue in a court case necessitates the expressing of a view by the court on a matter of political controversy, such view must be measured and go no more than is reasonably necessary to dispose of the issue at hand.

“Non‑adherence to these principles threatens the public's confidence in, and its perception of, the independence and impartiality of the Judiciary. A judge or judicial officer who expresses in public unwarranted or unnecessary political views risks compromising the appearance of impartiality and ability to hear any cases in which one’s political stance may reasonably be regarded as relevant.”

Then, the big announcement: Judge Kwok would be indefinitely prohibited from hearing political cases:

“The Chief Justice has in the past reminded all judges and judicial officers of these important principles, which are contained in the Guide to Judicial Conduct. He has also spoken to and reminded HH Judge Kwok of the importance of the above matters in discharging his judicial duties. The Reasons for Sentence referred to earlier have caused controversy in that there is a risk that some reasonable, fair‑minded and well‑informed persons could reasonably take the view that the aforesaid principles may have been compromised in that a wrong perception was given. Judge Kwok agreed with the Chief Justice. For these reasons, the Chief District Judge with the agreement of the Chief Justice has also decided that Judge Kwok should not for the time being deal with any cases involving a similar political context.”

While many felt the court should have done more and removed Kwok from the bench entirely, for supporters of the protest movement it was a rare moment of justice and a cause for hope. Most assumed that Judge Kwok would never again be in a position to treat protesters unfairly, even if he would still be on the bench. And many hoped it was a sign that the courts, led by the Chief Justice, would act to protect the judiciary’s integrity.

Yet even that was too much to hope for.

Chief Justice Cheung reinstates Judge Kwok, who is quickly appointed as a National Security Judge

In January 2021, Chief Justice Ma retired and was replaced by Andrew Cheung. Then-Chief Executive Carrie Lam had selected Cheung for the role the previous June. At the time, she praised Cheung’s “exceptional qualities, distinguished leadership and vision.” Given Lam’s history as a notorious human rights abuser, her endorsement was, to say the least, worrisome to those who were concerned about the future of the judiciary.

Cheung had already established his bona fides as a judge who saw the law as…shall we say, malleable to suit Beijing’s wishes. In 2016, he upheld a ruling disqualifying six pro-democracy lawmakers on appeal for not taking their oaths “solemnly” enough. Moreover, just before assuming his position as the top judge in December 2020, Cheung, along with two other judges, granted the Department of Justice leave to appeal the bail granted to pro-democracy media mogul Jimmy Lai. Cheung and four other national security judges subsequently reversed the lower court’s decision, resulting in Lai's return to prison, where he remains incarcerated to this day.

After taking office, Chief Justice Cheung moved to restore Judge Kwok to full presiding rights, citing Kwok's "expertise and experience" as well as "manpower shortages." Just three days later, Cheung created a new "advisory committee" to handle complaints against judges. He appointed himself chairman of the committee and filled it with judges and "members from the community" who were friendly to the establishment.

Then, shortly after Judge Kwok was reinstated, it was revealed that the Chief Executive had appointed him as a national security judge. Not only would Kwok be able to hear political cases again, but he would also hear the most politically sensitive cases of all: those against dissidents accused of political crimes under the national security law.

It's hard to believe that the three events—Kwok’s reinstatement, Cheung’s reform of the complaints process, and Kwok’s subsequent appointment as a national security judge—were unconnected. The Chief Executive “may consult” the Chief Justice on national security judge appointments under Article 44 of the National Security Law. If Chief Executive Lam, relaying Beijing’s wishes, informed the Chief Justice that she wanted to appoint Kwok as a national security judge, Cheung restoring Kwok to full duties would have been a prerequisite. Then, in order to ensure the issue could never arise again, Cheung stripped other judges of power to discipline members of the court and ensured that there could be no accountability for judges in the future without his personal approval.

No other judge or magistrate has been disciplined since.

***

Since his appointment as a national security judge, Kwok has ruled on four national security cases involving 15 defendants, all of whom were accused of nonviolent political crimes. He has sentenced each one to prison or juvenile detention. Now, he is overseeing the high-profile Stand News trial, and no one has any doubt as to what the end result will be.

Kwok’s transformation from an unassuming civil servant to a virulently pro-Beijing national security judge is tragic, and sadly far from unique. Many civil servants have betrayed their legal and ethical duties to advance the CCP’s political interests in Hong Kong. Most of them, like Kwok, have not acted out of conviction, but out of opportunism and fear: they have sought to advance their careers and avoid Beijing’s wrath by adopting the most radical and extreme pro-Beijing stances.