Impasse as Trudeau Fails With Assassination Claim

India denies claim, but not in private talks, say Canadian sources

By: John Elliott

Careful diplomacy could have avoided the current crisis between Canada and India if the two countries’ proud and stubborn leaders had tried to compromise over the controversial assassination of an alleged Sikh terrorist in Vancouver. Instead, they let their personal differences, plus 20 years of clashes over the activities of separatists originating from the Indian state of Punjab, to burst unexpectedly across world headlines.

It is now 10 days since Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau caused worldwide shock and astonishment by telling his country’s parliament that its security agency was “actively pursuing credible allegations of a potential link between agents of the government of India and the killing of a Canadian citizen.”

The “citizen” was Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a 45-year-old Sikh separatist with a string of charges against him in India, whose anti-India activities included organizing an unofficial referendum within the Sikh diaspora. He was shot dead on June 18 in an incident involving six men and two vehicles while leaving his gurdwara (temple) in Surrey, a suburb of Vancouver that has a large Sikh community.

The shock was that India could be accused of doing such a deed, especially just as it was emerging as a significant and responsible world power. The astonishment was that Trudeau would suddenly make such a bald, unsubstantiated parliamentary statement, challenging the increasingly influential Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose stock had just risen with his hugely successful G20 summit in Delhi.

Trudeau told parliament that he had confronted Modi on the allegation “in no uncertain terms” during the G20 weekend. That is not how Modi is accustomed to being treated, nor talked about, though it was a sort of payback for an Indian media briefing around the G20 that said Modi had “scolded” Trudeau over Candia’s repeated failure to deal with Sikh extremists. (Modi had earlier sidelined Trudeau during an embarrassingly self-destructive visit to India by the Canadian prime minister in 2018.)

In the “scolding” remarks that Modi’s office made public, Trudeau was blamed for allowing pro-Khalistan protests in Canada that were “promoting secessionism and inciting violence against Indian diplomats, damaging diplomatic premises and threatening the Indian community”.

Publicly, India has dismissed Trudeau’s assassination allegations as “absurd,” “politically motivated” and “unsubstantiated” (see MEA statement below). Modi told Trudeau they were “completely rejected.” On September 27, S. Jaishankar, India’s foreign secretary, said in New York that “we told the Canadians that this is not the government of India’s policy.”

Canada’s CBC news network however has been told by sources that “when pressed behind closed doors, no Indian official has denied the bombshell allegation.”

Maybe significantly, the question in New York had come from a former US ambassador to India. It happened during a seminar at the Council on Foreign Relations, where Jaishankar added that India had said to Trudeau, “if you have something specific, if you have something relevant, let us know, we are open to looking at it.”

Trudeau has not publicly released any details to support his claim, which is odd after 10 days. As Jaishankar implied yesterday, India seems to be waiting for details, though some must have been handed over during meetings between the two countries’ national security advisers that took place in Delhi over several days in August and September, including during the G20 summit.

CBC News has been told by Canadian government sources that they have gathered both human and signals intelligence that reveals communications involving Indian officials including diplomats present in Canada. Some of the information was significantly provided by the US, and Trudeau shared the allegations with Washington and other members of the Five Eyes (Australia, New Zealand and the UK) before the G20. These countries have urged India to co-operate with Canada in its investigations, but that does not seem to have happened.

Security experts suggest that India certainly has the expertise to carry out targeted assassinations and could well have also developed the essential political will over the past 10 years. There are reports that it has been behind killings in Pakistan but, experts suggest, it might need help (probably from Israel’s Mossad secret service) further afield in a place such as Canada.

“Israel has a remarkable record of targeted killing, an extremely close intelligence relationship with India, and a strategic relationship that encompasses the sanctum sanctorum of state security including space and nuclear,” ssays Pramit Chaudhuri, a former senior journalist and member of the National Security Advisory Board, and now the India head of Eurasia, a US political risk consultancy. “I would argue no other country in the world is as trusted by the Indian security apparatus.”

One of the curiosities is that nothing has been heard from Ajit Doval, India’s usually high-profile national security adviser, who held the talks with his Canadian counterpart and is in effect in charge of RAW.

How much of the alleged Indian involvement will ever actually emerge depends partly on how the current impasse is resolved. There are reports that President Biden and his top officials are trying to mediate between Trudeau’s assassination claim and India’s virtual denial and its insistence that Canada takes action against the extremists.

Mediation is urgently needed because there is now a risk that the furor could give the Khalistan cause some international credibility as a freedom movement, which it does not warrant because there is no mainstream or even significant Sikh minority wanting to disturb Punjab’s status in India.

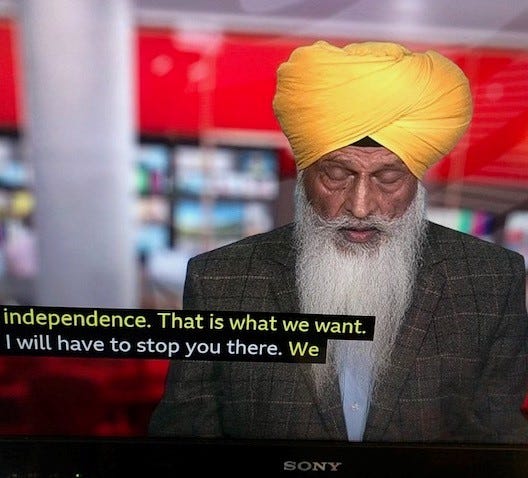

This risk emerged on a BBC Newsnight program on September 20, where the interviewer referred to Sikhs’ right “to campaign for their homeland.” This was in response to a leading Scotland-based Khalistan campaigner, Amrit Singh Gill, chairman of the separatist Sikh Federation of the UK, who said “People of Scotland have a right [to campaign so] why do Sikhs not have a right in India?”

That comparison may sound laughable, but the context was serious. Gill went on to say that, because of his activities, his family’s home in the Punjab had been raided last month by India’s anti-terrorist National Intelligence Agency. A relative had then been summoned to Delhi for questioning about his activities.

Taken against the backdrop of Modi’s strong Hindu nationalism, with reduced safety and status for Muslims and others, such media coverage could appear to human rights campaigners to be describing another example of minorities’ suppression that deserves international support, even though the actions of Khalistani supporters in Canada with alleged organized crime and terror activities are also getting considerable publicity.

India usually celebrates the activities of its diaspora abroad as emigrants have risen to the top of major companies such as Microsoft, Pepsi and Starbucks – and even to top political positions, notably in the UK with Rishi Sunak as prime minister. At least one Sikh is included in the list of successes – Ajay Banga, former CEO of Mastercard and now president of the World Bank.

For the Indian government however, it is the anti-India protests and other activities of the Khalistan movement that has caused increasing concern. The campaign, for the Indian state of Punjab (separate from Pakistan’s province of the same name) to be given independence, began 50 years ago. It led to an insurgency in Punjab in the 1980s, where there were genuine social, economic and other grievances.

Aided by Pakistan with training and supplies (including Chinese arms), the insurgency led eventually to the assassination in October 1984 of India’s prime minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. Tough police action suppressed the separatists by the early 1990s and the cause is now only pursued by an extreme fringe, often linked to rival gangs and groups. Punjab now has serious economic and social problems, but that is not leading to separatist activity.

During the troubled years, Sikhs fled abroad, notably to Canada but also the UK, Australia and elsewhere. Separatists then began to build the activity that led to the Nijjar’s shooting this June.

There are an estimated 770,000 Sikhs in Canada, a politically significant 2 percent of the population. It is the country’s fastest-growing religious group with the biggest number of Sikhs outside India. In other countries, they are far less significant, though in the UK the Khalistan activities have led India frequently to protest to the government.

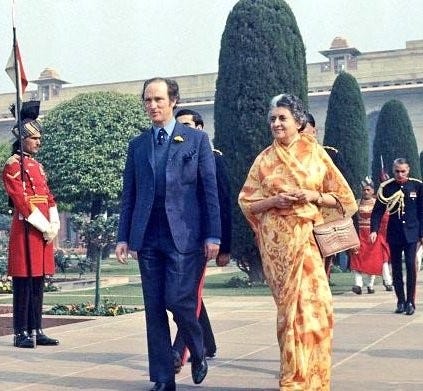

Canada’s soft reaction from the start caused Indira Gandhi to complain in 1982 to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, father of the current prime minister.

The motivation now is intensely political. A Sikh-led party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), is a small but essential partner in Trudeau’s governing coalition – if it withdrew, his government could collapse. Jaishankar dealt with that when he addressed the United Nations this week and said “political convenience” should not be allowed to determine a country’s response to “terrorism, extremism and violence”.

Astonishingly, Trudeau even failed to act when a 5 km-long parade on June 4 in Brampton, Ontario included a rather crude tableau that seemed to celebrate the assassination of Indira Gandhi. It included a female figure in a blood-stained white saree, with her hands up, as turbaned men pointed guns at her. A poster read “Revenge for the attack on Darbar Sahib” – a reference to Gandhi ordering the army into the Sikhs Golden Temple in Amritsar to remove heavily armed Khalistan extremists in June 1984.

To be a prisoner of a coalition partner to such an extent that this and other protests and gangster activities are allowed, does nothing for Trudeau's reputation: nor does his failure to substantiate his assassination allegation. For now at least, he seems the loser.

Modi on the other hand has been strengthened ahead of a general election next year because India has united behind the government in dismissing Trudeau's allegation, with almost unanimous condemnation across political lines and the media. India is also making the running with its allegations about the criminal and other activities of Khalistan separatists and their support in Canada, even though there is international awareness of what its RAW security agency could carry out.

John Elliott is Asia Sentinel’s South Asia correspondent. He blogs at Riding the Elephant.