Imran Khan Targets Military After Shooting

Ousted premier goes after generals although religious zealot attempted assassination

By: Salman Rafi Sheikh

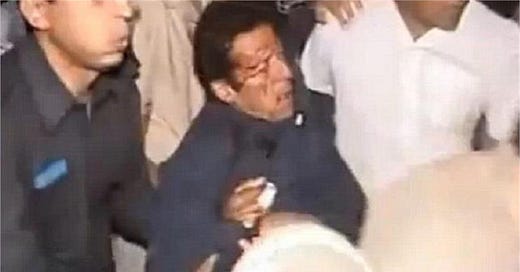

On Thursday, November 3, Pakistan’s former prime minister Imran Khan narrowly escaped an assassination attempt as he led his ‘long-march’ rally through Pakistan’s largest province, Punjab, to reach Islamabad, suffering a bullet wound in his leg.

The attacker – who was immediately apprehended and who said he does not have any group’s support, confessed to authorities that he was motivated by Imran Khan’s ‘disregard’ for religious rituals to kill him.

While it is rare for political leaders to avoid assassination attempts in Pakistan (many have been killed, including former prime minister Benazir Bhutto in December 2007), the fact that Khan survived has caused the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaaf (Pakistan Justice Party), which Khan leads, to unleash an intense wave of political attacks on the powerful military establishment for its manipulation of politics.

Khan targets the establishment

Between 2018 and 2022, Khan and the military establishment were allies, as Khan himself testified many times that he and the Chief of the Army Staff Qamar Javed Bajwa, were on the ‘same page’ vis-à-vis all political issues. But the Khan government’s failure to drive promised economic growth and the opposition’s success in directing the burden of the failure to the military establishment forced the latter to withdraw its support in favor of the opposition, triggering Khan government’s removal via a vote of no-confidence in April.

Khan’s ouster, however, didn’t mean the end of his political career. Instead of accepting the ouster as a fait accompli, he launched ‘The Free Pakistan Movement,’ alleging his ouster was masterminded by Washington and that the new government was implanted by the US because of his refusal to give the US airspace for Washington’s “over the horizon” strategy to conduct aerial strikes in Afghanistan to target al-Qaeda and the Islamic State militants.

While Khan’s theory of US interference was soon repudiated, what angered him the most was that it was the military establishment itself that exposed Khan’s anti-US populist narrative, as it confirmed there was no evidence of US interference.

Khan thus needed another rallying point to stay alive politically. By August 2022, within five months of his ouster, he turned his guns towards the military establishment and the latter’s support for the incumbent government. He was able to do that because of his popularity, evident from his party’s success in dominating by-elections in Punjab and convincingly defeating government candidates.

Confident of his support in Pakistan’s largest province – which has been the heart of military recruitment since colonial times – Khan re-launched his movement, now aiming at the military establishment. Within a day after the shooting, he appeared live on the media from the hospital, targeting the current regime and the military establishment although there was no link to the government.

Apart from naming the incumbent prime minister and the interior minister, Khan specifically accused a high official of Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Major General Faisal Naseer. Referring to General Bajwa, Khan said “This general is taking the country towards destruction” in much the same way, Khan continued, the military establishment drove Pakistan towards territorial disintegration in 1971 when East Pakistan, during the dictatorial rule of General Yahya Khan, became an independent state of Bangladesh following a brutal civil war and Indian military intervention.

The Pakistan military’s media wing, the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), called Khan’s allegations “baseless and irresponsible.”

Notwithstanding the ISPR’s response, no political party has so openly and explicitly named serving military and intelligence officials for their involvement in politics, including assassination attempts.

While Khan has not provided any proof of their involvement, he and his party have been successful in manipulating the scenario to their advantage by specifically targeting the regime.

Why is Khan so powerful today?

Imran Khan has never been as popular as he is today. His support base is not limited to the electorate only. Experts of Pakistani politics believe that Khan has a significant support base within the military establishment and even the judiciary. Many of his rallies are attended by former military officials, including retired generals. Former DG ISI Zaheer-ul-Islam also recently joined Khan’s party.

Most analysts familiar with the military’s internal dynamics believe that there is a lot of intra-military tension tied to some factions supporting Khan and some leading factions, led by the COAS, opposing Khan’s movement and politics.

PTI’s internal sources have confirmed to Asia Sentinel that their party has support within the establishment. This support also extends to the support that Khan has in the judiciary, evident from the sort of preferential treatment he received in a recent contempt of court case, where the Islamabad High Court gave him frequent opportunities to apologize to the concerned female judge Khan had threatened in one of his speeches in August 2022.

The court’s treatment of Khan’s case is markedly different from its treatment of former prime minister Yusuf Raza Gilani, who was convicted in a contempt case and disqualified for five years in 2012.

What does Khan want?

Khan’s movement is not for a strong civilian-led, parliamentary democracy in Pakistan. Relying on the support of powerful sections of the wider establishment including the judiciary, his movement is for a system in which he is all-powerful, holding unchallengeable authority. His political ideal is Riyasat-e-Medina, a system of politics and power created by Prophet Muhammad of Islam in AD622 and consolidated by the first four caliphs of Islam in the following decades.

While even Khan knows re-creating that system is impossible for all practical reasons, his justification for that ideal involves a justification for a powerful state dominated by one central leader, which, in this case, is himself.

Many of his opponents, therefore, see Khan’s politics as a version of fascism projected, for popular consumption, in a religious narrative. This is one key reason why Khan does not have any powerful political allies on his side, as he continues to project other political elites as “corrupt” and “thieves.” His opponents see his constant bashing of his opponents as evidence of his lack of interest in building a strong civilian democracy, a system that inevitably requires a larger political consensus involving all major parties.

But Khan’s PTI is yet to show any signs of such a possibility. In simple words, with Khan standing on the far end of the political spectrum with no political allies but with powerful populist and factional support, his possible success in toppling the regime and establishing his government would herald a new era of exclusionary politics reinforcing political persecution on the one hand and institutional meltdown on the other.

If, however, Khan can find a middle ground with other parties, the present crisis may herald a new era of civilian politics.