Almost lost amid the suspense of Malaysia’s November 19 general election is what appears to be the end of the 70-year political career of former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed, who was ousted from his Langkawi island seat by a PAS candidate. His fledgling Parti Pejuang Tanah Air – the characteristically pugnacious “Homeland Fighters Party” in English – appears to have been drubbed out of existence.

Why the 97-year-old former premier chose to contest the election was a mystery to some. He had stubbed his foot badly with his role in attempting to surreptitiously conjure up a Malay-superiority government in 2020 even while he was acting as prime minister of the ruling Pakatan Harapan coalition, refusing to keep his promise to hand over the premiership to opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim. The attempt, which became known as the Sheraton Putsch for the hotel in which the plotters machinated, collapsed when he backed out at the last minute.

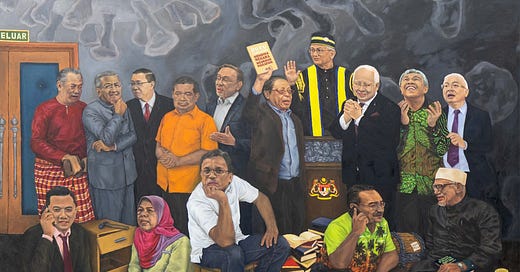

The putsch earned him deep condemnation and nearly wrote his end then, as well as kicking off two years of virulent political infighting and government paralysis that continued even after the November 19 election delivered a shaky compromise coalition of disparate elements headed by Anwar, Mahathir’s 75-year-old political foe. Keeping the United Malays National Organization in the coalition – a deal with the devil to stay in power – has cost Anwar the price of taking on a deputy prime minister with 47 charges of corruption pending against him.

But Mahathir’s decision to give it another go – which theoretically would have kept him in parliament til age 103 – wasn’t a mystery to everybody. Mahathir has spent decades making comebacks, starting when he was kicked out of UMNO in the late 1960s by Tunku Abdul Rahman, and ended up being among the Young Turks who ousted the Tunku after the 1969 race riots. He spent his entire career aggressively pushing what he regarded as unfair economic repression of the Malay race, particularly by the Chinese.

His efforts to raise Malay ownership and entrepreneurship too often ended in UMNO-related corruption of which 1MDB was the most outstanding but by no means unique example. His insistence on forming Malay-only parties successfully obstructed hopes of achieving multiracial rule which would by definition be focused on reducing rather than exploiting racial and religious differences. He was an advocate of the New Economic Policy formulated to uplift Malays but which ultimately constricted the economy, dulled entrepreneurship, spawned corruption – called rather colorfully Kleptonomics – and created a sense of entitlement for the majority race that hobbled the country.

Although his strenuous efforts to remake a pastoral Southeast Asian nation whose major exports were tin and rubber into an industrial powerhouse producing steel, cars, and the other accouterments of modern society mostly ended in debt and saddled the country with a series of white elephants, it was much as anything the chaos he unleashed after his 2003 retirement from politics that roiled the country. He handed over the leadership of the Barisan Nasional, which had been in power for 60 years, first to Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, then spent the next six years scheming to replace Badawi, a gentlemanly old-school Malay who wasn’t aggressive enough for Mahathir’s taste.

After playing a central role in ousting Badawi, he engineered as his replacement Najib Abdul Razak, who nearly wrecked the country, first creaming off billions as defense minister and becoming the architect of 1Malaysia Development Bhd, the state-backed investment fund that ultimately collapsed in a welter of spectacular corruption that cost US$5.4 billion and saddled the treasury with as much as US$15 billion in debt. The US Justice Department called it the biggest kleptocracy case in history.

Mahathir quit UMNO in disgust and formed Parti Pribumi Bersatu, a tiny all-Malay party that wagged the Pakatan Rakyat dog while he crisscrossed the country to denounce Najib. With Mahathir proposed as premier despite Bersatu’s tiny size, the reform coalition staged a political earthquake in 2018, then limped through 20 months of government – with Mahathir himself doing his best to sabotage some of the multiracial reform goals. That all ended with the Sheraton putsch.

This could be expected to write finis to Mahathir’s seven-decade political career, but don’t count on it. In the end, he remains as focused on the need for Malay political dominance as he was when he wrote his controversial book The Malay Dilemma touting special treatment for the Malays in the 1960s while in the political wilderness. His efforts at modernizing the economy are still evident in Malaysia’s admirable physical infrastructure but the problems created by his educational and religious policies are plain, as is the divide between Malays and others, particularly the often-demonized Chinese and Christians.

It is remarkable how ignominious his denouement has been, with every member of his fledgling party losing their campaigns and his son Mukhriz, who for two decades had hopes of succeeding his father in running the country, defenestrated as well. Malaysia will see how at 97, he intends to stir them up as a writer.

He has most recently taken to social media – Twitter – to accuse the nascent coalition of whitewashing the new deputy prime minister, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, of the 47 criminal charges. “In our legal system you are innocent until proven guilty,” Mahathir said. "If he can avoid (being judged guilty), and he is still innocent, then they will say he is qualified. They want him as DPM. There will be a lot of (inaudible) within the judiciary and the government. And the government will try to pressure the judiciary. They are not supposed to, but you know, they can change the judiciary.”

He should know. When the judiciary defied him in the 1980s, he fired the supreme court and began a campaign against the judiciary that eventually made it subservient to the government. Ironically, in his second short, 20-month reign as premier, he made an indelible mark on the judiciary by appointing fiercely independent judges. Those judges put Najib in jail for 12 years and now threaten Zahid. At the end of his career, it appeared that he had learned the value of an independent press and an independent judiciary.

If there ever was a devil spawn... this apanama son of kutty is it.