By: Shim Jae Hoon

A country proudly in possession of atomic and hydrogen bombs, even intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of hitting mainland US cities, and submarines that can launch missiles from below the ocean, surely North Korea is on the cusp of becoming a major military force. But it’s a country whose 25 million people are perpetually going hungry, with the regime running short on food to feed its populace.

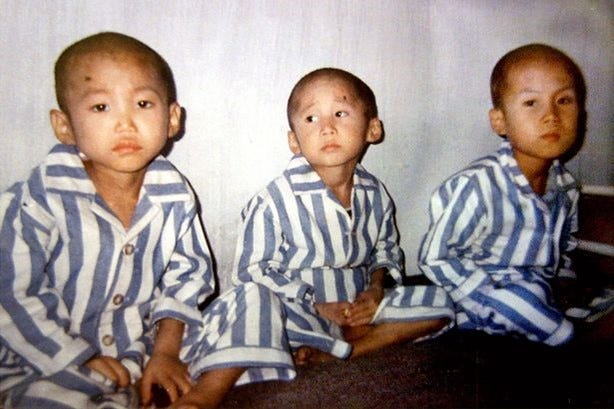

For a number of international aid agencies like the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), that’s not an ironic joke to be shrugged over. The last time the Pyongyang regime ran out of food, between 1995 and 2000, the regime under the second-generation Kim dynasty dictator allowed anywhere between half a million and three million people to perish in a famine that its propagandists euphemistically dubbed the “Years of Arduous March.”

Now under the third-generation dictator Kim Jong Un, the regime looks concerned but not enough to ask for emergency international aid. Just below the Demilitarized Zone in Seoul, the South Korean government is desperately fighting to stop the opposition party from forcing it to buy surplus rice crops from farmers obdurately refusing to cut down on their production. Probably out of shame or pride, Kim last year breezily ignored a South Korean proposal to send 50,000 tons of rice aid to alleviate another looming famine.

Instead, Kim appears hoping to ship munitions for Russia’s war against Ukraine in exchange for food from Putin, according to John Kirby, the US National Security Council spokesman. If that deal works out, a hungry North Korea is taking a major risk of extending the already lengthening Ukraine war.

For all its aggressive bravado, North Korea is a country in a perpetual hunger, not just because of its chilly climate and barren hills. Under a regime that mobilizes most of its economic resources to military sector, it plunged into a harrowing famine just 23 years ago with its traditional allies China and Soviet Union refusing to help. Cold-hearted Moscow and Beijing demanded market prices for their food aid, even as North Korea was broke.

Speaking at a Central Committee plenum session of the ruling Workers Party in February, the 38-year-old Kim Jong Un had no concrete proposals to tide the country over the crisis, other than ordering his cabinet to seek a “fundamental transformation” of the party’s agricultural policy. That however is unlikely to happen as the regime’s top priority rests on arms buildup, not raising food output. Like his father Kim Jong Il who left the agricultural issue largely in the hands of apparatchiks, Jong Un focuses on nuclear development. When the last famine erupted, Kim senior had the agriculture commissar simply executed on false charges of being an American spy.

Thus the North’s food crisis remains almost fatalistic. According to figures released by the Rural Development Administration in Seoul, the North’s total food production last year – including rice, wheat, maize, and potato – ran to 4.51 million tons, down 3.8 percent from the previous year. Owing to bad weather, fertilizer shortages, and backward farming, its annual food production has seldom exceeded 4.8 million tons at best, leaving annual shortage running to 1.5 or 1.8 million tons.

The shortage has turned even worse in the past two years with the Corona-19 pandemic forcing border shutdown, preventing imports from China and elsewhere. Food rations have been reduced significantly with imports being cut under UN Security Council sanctions triggered by its nuclear tests and missile launches. With border traffic reopening this year, the shortage is expected to lessen a bit, but not enough to help thwart widespread hunger, according to experts in Seoul. Even if doors are reopened for imports, the regime has run out of cash to purchase more food.

Problems affecting the shortage are so structural and fundamental to the North Korean system that few experts anticipate improvement anytime soon. Like the regime’s political and social controls, its agricultural policy is under strict party supervision. Collective farms provide manpower and some equipment, but they lack fossil-fuel-based inputs like fertilizers and mechanized equipment required for increasing outputs.

According to Dr. Kim Young Hoon, Seoul’s top expert on the North’s agricultural issues, its food shortages are unlikely to improve anytime soon unless essential inputs of modern farming and more independent management are offered to collective and cooperative farming units. The only way for the North to resolve the food crisis is for the party to relinquish its control, Kim told a recent seminar in Seoul. Put simply, it means the party allowing more independent management in the agricultural sector, but that would never happen in a country perpetually in the grip of dynastic control and a personality cult. A top-down system of control in “disregard of capital inputs,” he said, never works. You need more than just land and labor to increase crop yields, he said, adding capital input is essential. The North’s problem lies in its priority on arms spending, not on food.

Other specialists cite the problem of party doctrine on agricultural issues, such as the method of saturated planting in the hope of raising yields. But that requires higher fertilizer inputs and insecticides to produce higher yields. But that has been hampered by insufficient fertilizers and insecticides. In the 1990s, state founder Kim Il Sung caused disaster by instructing more terrace farming by cutting down trees on the hill, which caused landslides and floods during the rainy season, setting off an extensive agricultural fiasco and prompting famine.

Before his death in 1994, Kim senior – who has been posthumously designated the Supreme Leader in Perpetuity – promised his people daily meals of “beef soup with white rice.” Seven decades later, not only has that promise remained unfulfilled, it’s become a tragic joke as millions more face a potential second famine.