Pakistan Seeks to Join The Global Mineral Market

Why Islamabad’s mineral strategy requires immediate course correction

By: Salman Rafi Sheikh

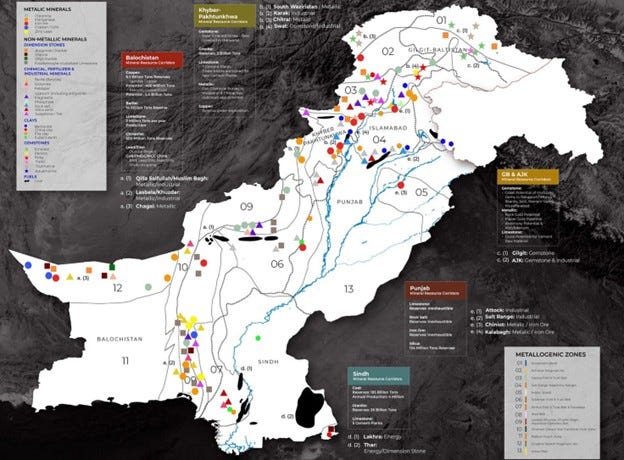

With more than 90 identified mineral types—including some of the most sought-after rare earth metals —Pakistan is positioning itself in the intensifying global race for control over critical minerals, putting it in unaccustomed bargaining territory with the Chinese decision to cut off the US from exports of the elements needed in computer chips for everything from cars to fighter jets to children’s toys.

The strategic pivot was formalized through the recently convened Pakistan Minerals Investment Forum, an event attended by more than 300 delegates and over 2,000 participants during which Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif declared the country open for international mining sector investment. Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar went a step further, expressing ambitions to transform the country into a “global mineral powerhouse.”

These moves come amid a shifting geopolitical landscape in which competition over mineral resources underpins the ongoing and broader "Global War on Trade”. As the dynamics show, the future of trade lies not just in tariffs or logistics but in access to the raw materials that power electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, semiconductors, and artificial intelligence technologies. In this context, Pakistan’s considerable lithium reserves—among the largest globally—place it squarely in the sights of major powers, notably the United States and China.

During the Biden administration, Pakistan remained largely peripheral to US strategic interests. However, recent high-profile visits by US officials suggest that the dynamic may be shifting. The UK-based Independent recently reported that the US, previously eyeing Ukraine for mineral extraction, is now increasingly looking toward Islamabad. The interest was underscored by a post-forum visit from Eric Meyer, a senior official in the US State Department’s Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, who conveyed Washington’s growing focus on Pakistan’s critical minerals sector.

While China already maintains a foothold in Pakistan’s mining landscape—especially through projects like Saindak and Reko Diq—the United States appears keen to counter Beijing’s expanding influence. The geopolitical tug-of-war over Pakistan’s mineral wealth is gaining momentum. But it raises fundamental questions: How should Pakistan harness its mineral endowments? Should it focus on geopolitical leveraging or industrial development? What kind of investment should it attract—and under what terms? Most critically, what development vision can prevent these assets from fueling conflict and inequality?

Broken Model

To address these questions, it’s essential to first scrutinize the existing model of resource extraction in Pakistan—particularly in the mineral-rich but underdeveloped province of Balochistan. Here, international firms typically extract raw materials through agreements that offer the state a share in profits, but often leave local communities with little to no material benefit. Despite hosting vast reserves of copper, gold, oil, gas, and the strategically important Gwadar Port, Balochistan remains Pakistan’s least developed province.

This exclusionary model has bred deep discontent. The decision to hand over Gwadar Port to China on a 40-year lease in 2013-14 – alongside tight fencing that has restricted local access –has exacerbated regional grievances. The province has witnessed a surge in attacks by separatist groups, including assaults on Chinese personnel involved in CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) projects. Repeating this model with critical minerals such as lithium and rare earth elements risks reinforcing these tensions on a potentially larger scale.

Legally, Pakistan’s constitution grants mineral ownership to provincial governments, while oil and gas reserves are jointly owned with the federal government. Yet recent developments, such as the Balochistan Assembly’s passage of the Mines and Minerals Act—followed by a similar bill in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly—suggest that Islamabad continues to centralize control, sidelining provincial stakeholders and reinforcing historical patterns of dispossession. In the long run, this is already a recipe for disaster.

Toward a New Development Model

If Pakistan is to avoid the pitfalls of resource dependency and conflict, it must rethink its approach. Prime Minister Sharif has claimed that the country’s mineral reserves are worth trillions of dollars—enough to break its chronic reliance on the International Monetary Fund. However, despite possessing the world’s fifth-largest copper and gold deposits, Pakistan’s mineral sector contributes only around 3 percent to GDP and less than 0.1 percent to global mineral exports.

Clearly, extraction alone is not enough. Pakistan needs to move up the value chain from being a supplier of raw materials to a producer of finished goods. This requires developing domestic industrial capacity to manufacture finished products. Not only would this create employment, but it would also reduce the country’s dependency on foreign capital and supply chains for extraction and share in revenue only.

However, Pakistan should take a lesson from Indonesia, which has been struggling with downstream processing for more than a decade, ending up with largely Chinese-owned production and massive corruption. Doweenstram processing of rare earth minerals, like mining them, can also lead to environmental disaster, as China has learned to its sorrow.

Admittedly, building such an industrial base in security-sensitive provinces like Balochistan and KP poses major challenges. Yet failure to do so will likely exacerbate existing unrest. In Balochistan, continuing the status quo will likely intensify separatist sentiment, eroding any hope of long-term stability—let alone foreign investment.

At the international level, Pakistan also faces pressure from foreign powers eager to secure mineral access on favorable terms. US officials, including Secretary of State Mark Rubio, have reportedly suggested that bilateral relations could improve if Pakistan grants American companies access to its critical minerals. However, there appears to be little US interest in investing in domestic industrial development within Pakistan—only in securing raw material supplies.

Accepting such deals without demanding value-added investments could cement Pakistan’s place as a peripheral player in global supply chains, locked into a cycle of low-value extraction and high-value imports.

Ultimately, Pakistan’s mineral wealth represents both an opportunity and a threat. If mismanaged, it risks becoming yet another “resource curse,” deepening inequality, fueling internal conflict, and reinforcing global dependency. If strategically leveraged—with attention to industrialisation, provincial equity, and geopolitical balance—it could mark the beginning of a new development trajectory. The choice lies in what kind of economic vision the country chooses to pursue—and whether it is willing to break from past patterns to realise the full potential of its natural endowments.

Dr. Salman Rafi Sheikh is an Assistant Professor of Politics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). He holds a Ph.D. in Politics and International Studies from SOAS, University of London. He is a longtime regular contributor to Asia Sentinel.