The Philippines’ Corruption-Ridden Prison System

A journalist’s murder shines a spotlight on a rotten, decades-old correctional regime

By: Viswa Nathan

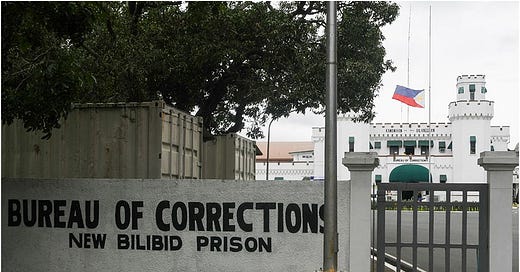

The October 3 murder of the Philippine broadcast journalist Percival Mabasa—also known as Percy Lapid—by a motorcycle-borne assassin as Mabasa drove into his gated community, followed by the death of Cristito “Jun Villamor” Palaña, an inmate in the country’s high-security New Bilibid Prison, has yielded more than what the crimes were expected to deliver.

The killings have brought to focus what makes the Philippine penal system—perhaps other establishments too—rotten: corruption, cold-blooded revenge against anyone demanding accountability from those in authority, and fearless misuse of power.

It has also inspired Representative Robert Ace Barbers to move a bill in Congress to tighten prison security and prevent contraband items from entering correctional centers, a policy made mockery of by New Bilibid. “The proliferation of contraband in prison has remained a perennial problem in the country,” said Barbers. “Its never-ending presence inside the correctional facilities has now transformed our prison institutions into breeding grounds for continuing criminality.”

As details of the latest crime involving the prison unfolded, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said he was bothered by the linking of Bureau of Corrections chief Gerald Bantag to the crime and ordered Bantag’s suspension although Bantag remains free so far despite the gunman’s confession linking him to the crime, a depressing reminder of the widespread impunity that has long kept high-ranking officials free of prosecution.

“I guess he (Bantag) established his own fiefdom there in prison,” the president said. “That’s why he moved with no fear of being punished.” It was a candid observation of how a succession of previous administrations neglected proper supervision of correctional facilities and let them degenerate into a pathetic state.

Against that unnerving realization, and in keeping with his election promise of a unity government for a better Philippines, the president reached out across political barriers and named the retired General Gregorio Catapang, Jr. as the officer in charge of the bureau of corrections. Catapang, formerly a rebel soldier who plotted with others against the dictatorship of Marcos Sr., was chief of the armed forces during the administration of President Benigno Aquino III, and also close to the Aquino clan.

The challenge that Gen. Catapang faces, now coming out of retirement, is monumental. “We have to look at and see what happened here, why did we come to this, what went on inside the prison,” said Marcos before appointing Catapang to the task.

Soon after taking charge, Catapang discovered a large and deep tunnel dug below a swimming pool close to the director’s residence and leading to a river nearby.

But then this was not the first time a tunnel was discovered in the NBP compound. In July 2014, a tunnel was found at a pipe-laying project by a water concessionaire. It was inside the maximum-security compound that served as a detention facility for former soldiers and police officers. Bureau officials then said it was merely part of their “drainage system” built in the 1930s.

Now Bantag, charged with the murder of Lapid and Palaña, says that he ordered the construction of a diving pool because he wanted to teach scuba diving.

Its discovery came following the capture of some 12,000 contraband items—mobile phones, laptop computers, drugs, and 7,500 cans of beer—smuggled into the prison compound. Prisoner Cristito Palaña, who allegedly was the middleman for the order to assassinate Percy Lapid, was also found to possess a mobile phone. But he was killed just hours after Joel Escorial, the confessed assassin of Lapid, surrendered to authorities. Palaña was first said to have died of a heart attack, but a subsequent investigation concluded he had died when a plastic garbage bag was stretched over his head.

Then again, this is not the first time such smuggling activity has been spotted. New Bilibid and other prisons in the country have long been known for irregularities. There have been reports about wealthy criminals serving lengthy prison terms, building comfortable homes inside the prison compound, and leading a carefree life long before Bantag took charge.

CNN Philippines reported just over three years ago that a senate hearing had learned of mobile phones being sold to convicted drug lords at New Bilibid for up to PHP2.5 million, well over US$40,000. The report also said 16 police officers deployed at the prison to augment security were under investigation for smuggling contraband items into the prison compound. Besides, witnesses reported to have said there’s a 24-hour casino inside the penitentiary, and high-profile inmates paid prison guards PHP30,000 to allow female entertainers to stay in their cells overnight.

While Bantag’s culpability in the illicit activities and the murders of Lapid and Palaña, is a matter for the court to determine, he has assumed the role of a whistleblower, calling for the resignation of Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla and warning the president to watch out for where he receives his information from.

Bantag was named Bureau director when former president, Rodrigo Duterte, fired the previous director, Nicanor Faeldon, in early September 2019 for signing an order defying a presidential directive. That order was for releasing 1,900 heinous crime convicts under a new law that allowed convicts early release based on good conduct time allowance. Among the prisoners Faeldon selected for release was former Calauan, Laguna, mayor Antonio L. Sanchez, serving seven counts of 40-year terms for the rape and murder of University of the Philippines student Eileen Sarmenta and the murder of her boyfriend and fellow UP student Allan Gomes in 1993, and a double life term for two other previous murders—altogether 360 years. Faeldon’s action sparked a public uproar.

To fill the vacancy left by Faeldon, Duterte picked Bantag, who then was with the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, which supervised all district, city, and municipal jails in the country.

Whether or not the former president was then aware of Bantag’s career history, which, according to published media reports, was sprinkled with controversies, is now irrelevant. What is essential now is while bringing the culprits in the New Bilibid episode to justice, a process must also begin to make correctional centers indeed what they should be.

The history of Bilibid prison is a sad tale. The old Bilibid prison that the Spanish rulers built in Manila in the mid-1800s was for 1,127 inmates. But with rising incidents of crime, the number of inmates rose to 4,800. Thus, the new masters of the country, the commonwealth that ruled before the Japanese overran the country in World War II, decided in the 1930s to build a new facility some 30 km south of Manila in Muntinlupa and in 1940 moved all inmates of the old facility to the new one, called the New Bilibid Prison. Its projected capacity then was 6,435 inmates. As of November 2021, it housed 28,545.

Clearly, building additional correctional centers to alleviate overcrowding in present facilities, would simply be an affirmation of the government’s failure to tackle the causes that promote crime. The proposals in Representative Barbers’ bill also do not target these causes, they only aim at the symptoms.

The questions the episode has thrown up are clear: Will President Marcos go beyond solving the latest New Bilibid crisis and take steps for the society to rid itself of the factors that breed crime? And will the people at large support such an initiative for building a better Philippines?

The Americans had nothing to do with New Bilibid. It was built during the Commonwealth when the Philippines was already autonomous and self-governing preparatory to full independence. In working out the requirements for independence including shiftin the government's policies and facilities to independence, a more modern penal system was envisaged including building a new national penitentiary. Over the past half century there has been little to no political benefit to pursuing humane reforms in the prison system and so neither funding nor actual changes to the penal regime have been seriously attempted as a result.