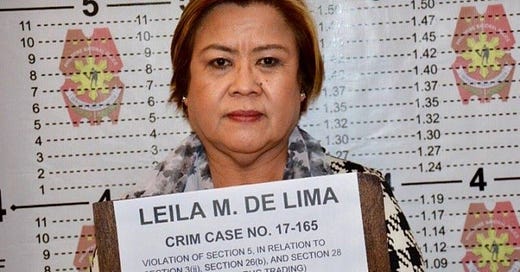

Philippines’ De Lima a ‘Prisoner of Conscience’

Marcos appears unwilling to free his predecessor’s political prisoner

By: Viswa Nathan

If justice delayed is justice denied, the Philippines could well be among those leading in that category. A recent victim is the former justice secretary and later senator, Leila de Lima, 64, who was arrested soon after Duterte assumed the presidency almost seven years ago. She remains in custody under the rule of Duterte’s successor, Marcos Jr. despite witnesses against her having recanted their testimony. She has been named a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International and other organizations.

No matter the charges Duterte’s justice secretary, Vitaliano Aguirre, presented against De Lima to convince Judge Juanita Guerrero to conclude that there was “sufficient probable cause for the issuance of Warrants of Arrest” against her and two co-accused—Rafael Marcos Z. Ragos, a former chief of Bureau of Corrections, and De Lima’s driver Ronnie Palisoc Dayan—the popular view outside the court was that the court order resulted from a calculated political vendetta.

De Lima’s camp filed a motion to quash the petition, but the court issued the arrest warrants without hearing it. De Lima’s lawyer, Alex Padilla, called that decision a “pre-judgment” on the judge’s part.

Still, when the court order was about to be carried out on February 24, 2017, De Lima rose to a new height in her crusade to expose Duterte’s alleged human rights violations and extra-judicial killings since he was mayor of the southern city of Davao. She voluntarily surrendered to the arresting team saying, “it’s my honor to be jailed for the principles I am fighting for.” The truth, she said, would come out at the proper time. Six months before, she had said she was willing “to be shot in front of Duterte if the drug allegations against her are proven true.”

The tiff between Duterte and De Lima has a long history.

When she headed the Philippine Commission on Human Rights, De Lima had investigated the extra-judicial killings suspected to have been carried out by the so-called Davao Death Squad, allegedly under the then Davao mayor, Duterte. After Duterte was elected president in 2016, the newly-elected senator began raising concerns about a new wave of extra-judicial killings as part of his war on drugs. She made two privileged speeches in the senate and filed a resolution initiating a probe into these killings. She presented Edgar Matobato, who claimed to be a former member of the Davao Death Squad, to the senate hearing where he said that Duterte condoned some 1,000 murders carried out by Davao-based vigilante groups. Matobato also confessed that as a member of the Death Squad, he alone killed at least 50 people.

Duterte was not the only powerholder De Lima rubbed on the wrong side during her long public service. As the justice secretary to former president Aquino III, she led a raid at the New Bilibid Prison, where 19 drug lords were found to have luxurious quarters, and the police confiscated illegal drugs, weapons, and several other smuggled items. She also prosecuted a few prominent figures, including former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo for misuse of development funds and electoral misconduct.

In a country where who scratches whose back plays a more vital role than rectitude and impartial justice, De Lima’s senate actions brought her to the high-risk territory. For Duterte, they opened the old wounds, and he started a no-holds-barred reprisal to destroy her reputation in every possible way. He went on television alleging that the senator had an illicit affair with her driver Ronnie Dayan who, he claimed, functioned as De Lima’s collector of protection payoffs from drug lords. During the congressional probe on illegal trafficking in the New Bilibid Prison, Duterte’s justice secretary Aguirre presented convicted drug lords, former prison officials, and police officers as prime witnesses against De Lima.

A month after Duterte began his counteraction against De Lima, Senator Alan Peter Cayetano, the unsuccessful running mate of Duterte in the 2016 presidential race, led 15 other senators in the 22-member chamber to remove De Lima from chairing the Senate Justice and Human Rights Committee that was investigating extra-judicial killings.

It’s unlikely that De Lima was ignorant of the consequences of her move. But she seemed willing to tread the path even devils would deter.

For such determination, she has won accolades. In 2016, the Washington-based Foreign Policy magazine listed her as one of the 13 global thinkers in the “Challengers” category “for standing up to an extremist leader.”

In 2017, Time magazine named her as one of the 100 Most Influential People, notably in the category of “speaking truth to power.”

In 2018, Amnesty International awarded her as the Most Distinguished Human Rights Defender.

As she entered her seventh year in confinement at Camp Crame, the national police headquarters, late last month, she was still waiting for her day in court. Over this period, and to the prosecution’s chagrin or De Lima’s delight, three of the prosecution witnesses recanted their testimonies.

Ragos, the former Bureau of Corrections chief, who had entered a testimony stating that he received money from Bilibid Prison inmates and sent it to De Lima through her driver Dayan, recanted last April, as Duterte’s presidency was coming to its close. He claimed that Duterte’s justice secretary, Aguirre, coerced him “to admit something that did not happen.” Aguirre, of course, denied it.

The same month, suspected drug lord Kerwin Espinosa reversed his testimony. Kerwin’s father, Ronaldo Espinosa, the mayor of Albuera in Leyte Province, had previously corroborated allegations that De Lima had benefited from his son’s illegal drug activities. Kerwin testified that he gave De Lima PHP8 million for her senatorial election bid in May 2016.

But last April, Kerwin Espinosa pleaded in an affidavit that he was “coerced, pressured, intimidated, and seriously threatened by the police” to testify against De Lima.

The third prosecution witness to recant was Ronnie Palisoc Dayan last May. He was captured while on the run, avoiding testifying at the Senate hearing against De Lima, and coerced to become a prosecution witness against his former employer and lover. He claimed the House justice committee chairman, the late Reynaldo Umali, asked him to lie about receiving drug money for De Lima.

With all key witnesses thus recanted, many ask why President Marcos’ justice department wants to continue the case.

A fortnight before Marcos took office, the then-justice secretary, Menardo Guevarra, who was leaving office with President Duterte, had indicated the retiring president’s mindset. He said the charges against De Lima would not be dropped just because some witnesses had recanted.

In mid-October, President Marcos said that exercising his executive authority to order the Justice Department to dismiss the charges would be “interfering” with the judicial process in motion.

Some in the legal circle see it as a copout. “The president wouldn’t dare act on such an issue which is too sensitive to his powerful predecessor and ally,” said one of them.

However, Marcos seems to be seeking a way out. His justice secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla recently said if De Lima’s camp filed a habeas corpus petition, the government would not oppose it, thus leaving the court to rule on it.

De Lima was acquitted of one of the three drug charges against her. And late last month, she asked the court in a handwritten petition to dismiss the remaining charges against her since three prosecution witnesses had retracted their testimony against her.

How would the chips now fall is as much a concern for Duterte as it is for De Lima.