Over the past year, the world has witnessed an increasing struggle between the so-called revisionist forces and the status quo ones, if the US and its allies together represent the status quo, and China (and Russia) represent the so-called revisionists. The actions and policies of the US and its NATO allies are in a struggle to preserve a Western-dominated global political system.

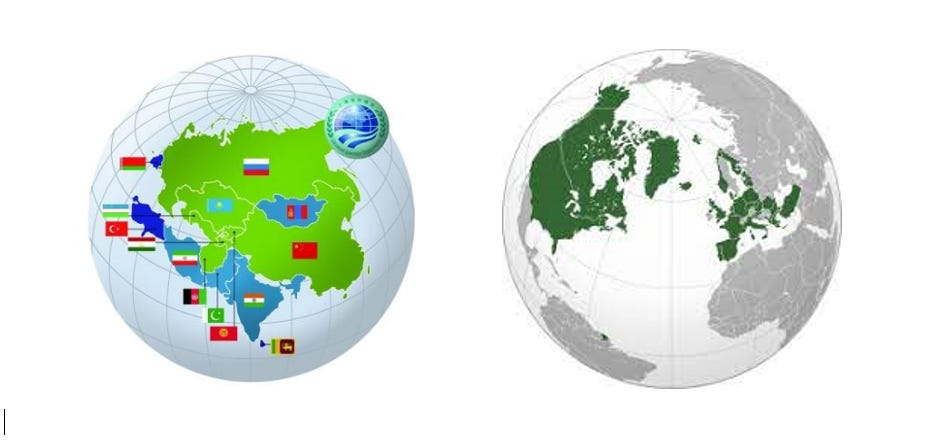

But this isn’t as important as NATO’s expansion outside of Europe. In this context, NATO’s recent moves to develop partnerships with Asian countries such as Japan, and the opposing eight-member Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s (SCO’s) moves to include countries like Saudi Arabia as “dialogue members” represent the ongoing struggle between these two forces. Although NATO is considerably more robust than the SCO as an intergovernmental military alliance between 31 member states who share military interoperability and whose core members run coordinated military exercises, diplomatically the SCO has it rattled.

For NATO, the trick is to expand into Asia and build a geopolitical ring of allies situated closer to its core adversaries. For SCO, the trick to is wean as many allies from the old West-led system as it can to expand its geopolitical clout and global footprint as a counterweight. Thus the struggle, regardless of who ultimately prevails, indicates that the world is no longer unilateral and that a solid turn towards multipolarity has already increased.

In this context, when a NATO delegation recently visited Japan, the message it delivered to Japan’s leadership was clear: the so-called revisionist forces are as much a threat to Europe/West as to Japan in the Indo-Pacific. As Lieutenant General Diella of NATO reminded his Japanese hosts, “I have seen first-hand that what happens in Europe matters to you, just as what happens in the Indo-Pacific region matters to NATO. Your support to Ukraine has been significant, demonstrating your engagement as a security provider on a global scale. Our security is deeply interconnected and so must be our cooperation, which is rooted in our shared values, and our shared vision – of a free, peaceful, and prosperous world.”

It is the same underlying reason that drove Saudi Arabia to join the China-led SCO, which in some measure is a constellation of states that don’t trust each other, for instance India and Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Iran, and whose only common interest appears to be a desire to blunt US influence. The other members are Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan with a flock of pilot fish as observers. Saudia’s move comes against the backdrop of its deteriorating ties with the US – a deterioration that can be attributed to the Biden administration’s decision to implicate Muhammad bin Salman (MBS) in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul. While implicating MBS didn’t really dethrone him, it had the effect of making Saudi Arabia introduce a major shift in its foreign policy.

When Saudi Arabia announced in March that it would join SCO, it coincided with Saudi Aramco’s decision to raise its multi-billion-dollar investment in China. Two separate deals will allow Aramco to supply 690,000 barrels a day of crude oil to China, making Aramco China’s top oil provider. Seen in the context of the Saudi decision to join SCO, this deal appears to have much deeper geopolitical implications than simply commercial gains for Riyadh. This solidifies its ties with the anti-US, counter-hegemonic, revisionist bloc.

For Riyadh, by allying with China (and Russia, as is most evident from Riyadh’s decision to keep the OPEC+ pact with Russia intact at the expense of the US and European interests), it can play a much bigger role in the world than it has played as a US ally over the past few decades. Joining SCO doesn’t simply make it a junior player within this new world order; rather it means becoming a major center of power in a new world order.

Riyadh’s decision is having a boomerang effect, with many other countries from the Middle East likely to follow its lead. Turkey, which has its own global ambitions, is also eyeing SCO membership. It has been a “dialogue partner” of SCO since 2016, and recently upped its campaign to become an observer and eventually become a full member. Turkey’s possible SCO membership could be as critical as Saudia’s, but for different reasons. Turkey is a NATO member and its shift towards a bloc that NATO is seeking to counter could potentially compromise the alliance from within – an alliance that operates on the basis of unanimity.

Turkey, which has already bought the Russian S-400 air defense system, is at odds with the US and NATO. Joining SCO could not only mean that Turkey will have much easier access to Russian and Chinese defense systems and equipment, but also a much stronger ability to resist US pressure, the (possibility of) US sanctions, and access to alternative routes of trade.

Let’s not forget that many SCO countries are now willing to trade in currencies other than the US dollar. In fact, in their September 2022 summit, SCO leaders agreed to increase trade in national currencies. In the recently held meeting of the SCO Foreign Ministers in India, Russia’s Lavrov reiterated the message. It is a message attractive for countries either unhappy with the US (Saudia, Turkey, Pakistan, etc) or willing to part ways with the US in order to decrease their dependence on the US currency.

This is also an attractive message for countries like India trying to carve out a space for their own sake in the changing international order. India, like Turkey, is also part of both blocs. It has deep ties with the US, and it is also a member of the US-led (anti-China) Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD).

But the fact that the China-led SCO held its summit in India with Chinese consent, and despite Pakistani concerns and reservations, shows how even China (and Russia) are actively seeking to prevent India from becoming a US strategic ally. They appear to be willing to offer India wide enough space to project its global ambitions within a multi-polar world.

For the US and its NATO allies, this is a challenging situation. Can they reverse or manage it? It remains a moot question, but a recent surge in US diplomatic efforts to re-engage with Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific does indicate a clear intent: a pushback against Chinese (and Russian) expansion.

What this bloc does need, or what it has so far lacked, is a comprehensive economic package or an effective, realistic trade plan. It will need to shift its sole emphasis on security and military affairs to undercut its Chinese footprint. In other words, while bringing NATO to Asia may work, it is certainly not going to be enough.

Read related story: The Asian Ripples From Russia’s Ukraine Gambit