Singapore’s ‘Fake News’ Law: Targeting Critics, Opponents

Fake news is what the government says it is

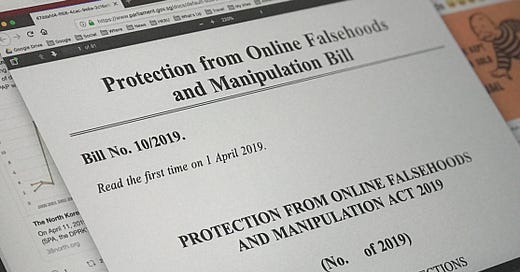

When the Singapore government passed its “Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act” in May of 2019, commonly known as POFMA, the fear was that just about any minister could use it against pretty much any target and that it would serve as a deterrent to political free speech.

That seems largely to have come true, the law’s critics say. Since its passage four years ago as Singapore’s “fake news law,” it has been used an even 100 times, according to a database compiled by Terry Xu, the editor of The Online Citizen, a news portal once based in Singapore but now forced to operate in Taiwan as its license was suspended. The heads of 13 of Singapore’s 16 ministries have invoked the law, leaving only the Ministries of Defense, Culture, Community and Youth, and Sustainability and the Environment which haven’t used it yet.

At least a third of POFMA charges – 35 – have been brought against opposition political parties and political figures such as the Singapore Democratic Party, its leader Chee Soon Juan, The People’s Voice party and its lawyer-leader Lim Tean, and Alex Tan Zhixiang, a self-exiled dissident and editor of the now-dissolved Temasek Review, according to independently collated public records of POFMA usage in 2021 by Teo Kai Xiang, a Singaporean graduate from Cambridge University.

“As widely predicted and feared upon its passage, Singapore’s fake news law is being abused by authorities to stifle independent news reporting and critical voices,” said Shawn Crispin, the senior Southeast Asia representative for the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists. “It shows clearly that authorities view the law as a tool to censor free reporting under the thinly veiled and dishonest guise of protecting the Singaporean public from misinformation and fake news. The law as written and applied should be scrapped, if Singapore still has any interest in portraying itself as a functioning democracy."

Crispin’s concerns are echoed by every major press and human rights organization including Reporters Without Borders, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and many more. “POFMA has only worsened the press freedom situation in the ‘city-state’ and shown the true face of the Singaporean government: an aggressive government that does not tolerate criticism, is prepared to fight outside its jurisdiction, and wants at all costs to set itself up as the "Ministry of Truth," said Reporters Without Borders.

One of the big problems pointed out by Terry Xu is that far from what Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam promised in Parliament as the legislation was being debated, “Setting aside the absurdity of asking the minister who issued the directions to withdraw the orders, my personal experience with the appeal process at the High Court has been costly and lengthy. Any ordinary individual or entity that receives a POFMA direction would find it challenging to consider filing an appeal even if they did not communicate a statement of falsehood as claimed by the ministers.”

The result is that defendants have simply knuckled under and carried corrections rather than fighting the charges. People’s Voice head Lim said he has been charged four times with the result that his website simply carried the government’s version at the top, in the prescribed font and type, for a solid month.

“The courts are forced to spend an absurd amount of time deciding disputes when the government could easily explain its position and allow the people to decide what is the truth,” said Lim. “The legal process to resolve disputes is anything but inexpensive.”

By and large, government officials have resisted going after overseas targets, for example, shying away from invoking POFMA against erroneous claims made on April 14 by the locally based Private Banking Industry Group over a report in the London-based Financial Times regarding the Monetary Authority of Singapore asking financial institutions in Singapore to keep quiet about the sources of money flowing into the country. Singapore has long been a repository of questionable funds stolen in Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and other state-linked foreign companies deposited in Singaporean banks.

The government did bring charges against a legal advocacy NGO called Lawyers for Liberty, based in Kuala Lumpur, for repeating a published statement charging that Singaporean jailers had used cruel and unusual methods in the hanging of Malaysian drug mules.

Along with Asia Sentinel, which was charged on May 26 over what was termed an erroneous news report and later banned from reaching readers in Singapore, Lawyers for Liberty refused to apologize or amend its report. It has sued for relief in a Kuala Lumpur court, arguing Singapore law doesn’t apply in a different sovereign state, and subpoenaed Singapore Law Minister K Shanmugam to appear. So far, he hasn’t done so and appears unlikely to, said Zaid Melet, the head of the NGO.

(Although Asia Sentinel printed Singapore’s demand for a correction – along with its reasons to refuse to write a correction, contending the report was accurate – the regional news portal was ordered blocked on June 2 by Minister K Shanmugam through the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA). As with Lawyers For Liberty, Asia Sentinel contends the law doesn’t apply since the publication is legally domiciled in the United States.)

Given the timing of POFMA’s introduction a few months prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, about half of its usage to date has been targeted towards countering Covid-19 and Covid vaccine-related misinformation. This has provided the government with a convenient foil of legitimacy for POFMA, as a law to be used in protecting public health and social stability.

Amnesty International earlier this year charged the law “has been repeatedly used by authorities to target critics and political opponents. Of particular concern is the law’s lack of clear definition of what constitutes a falsehood.”

Fears the law would be used to target government critics “were confirmed when government ministers issued multiple correction directions under POFMA for posts on social media within the first two months of the law’s enactment in 2019,” Amnesty International said. “These correction directions were issued against Facebook posts made by critics of the ruling People’s Action Party. Social media companies such as Facebook have expressed concerns over being forced to comply with POFMA orders, including the blocking of the pages of independent website States Times Review.”

In a rare domestic example of dissent, Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon in September 2020 described POFMA as a “blunt tool” that could be misused by government ministers to suppress “responsible journalism” publishing negative allegations and narratives about the Singapore Government in a ruling against the PAP government’s POFMA usage against the Singapore Democratic Party and The Online Citizen.

In his judgment, Menon stated that “acknowledging Singaporeans’ right to know ‘that a whistle has been blown’ is not the same thing as agreeing with the whistleblower — a media outlet carrying a whistleblower’s allegation is simply ‘reporting the debate’.”

Menon’s colleague, Justice Phang also remarked that the government’s justification for the parameters it chooses to use in deciding whether to invoke POFMA would “drastically reduce the category of news that can be reported and may upset the “delicate balance” between free speech and combating the dissemination of falsehoods.”

Yet, on May 27, 2020, Shanmugam attempted to extend his invocation of POFMA against criticism of the law on Facebook by Alex Tan, by bringing up the possibility of prosecuting him for contempt of court.

When opposition politicians raised the possibility of Singapore introducing a Freedom of Information Act in 2011, government ministers criticized not only the idea of an FOI Act but also the insinuation that local society mistrusted its mainstream media due to its state-controlled nature. When statistical data was requested in Parliament by opposition politicians to scrutinize the labor employment situation in Singapore between local citizens and foreigners, the government’s response was to immediately question the intent of requesting such data before dismissing the request as an irrelevance “as long as the ruling party delivered jobs for Singaporeans.”

That raises the question of whether POFMA is truly in the best interest of everybody when the imposition of information asymmetry by the government. The absence of FOI means that the government gets to act as the sole gatekeeper of truth on any topic pertaining to Singapore.

Andy Wong Ming Jun, a Singaporean dissident who remains in exile in the UK, contributed extensive research for this report