Singapore's Social Engineers Run Out of Ideas on Population Decline

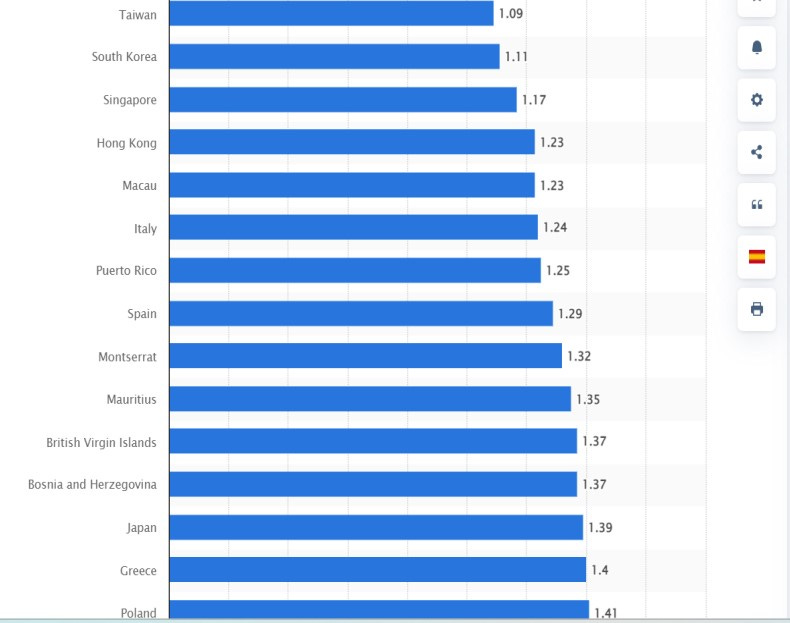

Couples forsake babies, elders dwindle, leaving government to look to immigration

The news earlier this week that Singapore’s total fertility rate has dropped to a record low of 0.97 in 2023, a decline against even last year’s record low of 1.04, and another record decline to 1.12 in 2021, is depressing testimony to the fact that the government has been trying to raise without success total fertility for 40 years -- since 1984, when officials suddenly cottoned to the fact that the city-state’s women no longer wanted to have children. (Total fertility is measured as the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime.)

At the same time, as the prime minister’s office pointed out in its latest overview of population trends, the proportion of citizen population aged 65 years and above is rising, “and at a faster pace compared to the last decade. Large cohorts of ‘baby boomers’ have begun entering the post-65 age range, with the proportion of citizens aged 65 increasing from 11.7 percent in 2013 to 19.1 percent in 2023. “By 2030, around 1 in 4 citizens (24.1 percent) will be aged 65 & above.”

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, at a recent Forbes Global CEO Conference, suggested that, with help from immigration, a fertility rate of 1.3–1.4 might be enough to meet the country’s needs. He is determined, he told the conference, to meet this challenge. But that appears to be wishful thinking. While Singapore’s population has continued to increase steadily, much of it through massive in-migration, the city-state is hardly alone, with birth rates falling in urbanized societies all over the planet including in China, where officials have not only discarded the one-child policy but the two-child policy as well. No nation has figured out the answer to falling population.

But Singapore has been at it longer than most and has become famous for social engineering to attempt to change its citizenry’s habits, including getting them to stop smoking, eschew road rage, stay away from drugs, and, in one famous 1988 campaign, not urinate in public housing lifts. The Straits Times, the government-backed newspaper, has constant public education campaigns on whatever issue the government feels is important in keeping the citizenry headed in the right direction, generating a certain amount of schadenfreude when a campaign doesn’t work. Population control is at the top of the list.

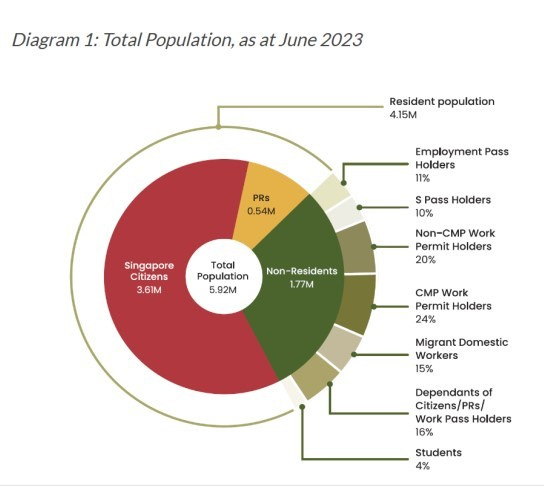

Some 2.31 million of Singapore’s 5.91 million residents are immigrants, or nearly 40 percent. As a 2023 World Bank report notes, “Migrant workers, across all ends of the spectrum, act as a buffer against macroeconomic cycles, allowing for rapid expansion of the labor force while taming inflation during booms, and moderating the impact of busts on resident employment through selective attrition of the foreign workforce.”

But that hasn’t solved the problem of adding more home-grown Singaporeans. The government’s social engineers have resorted to heroic measures to attempt to raise the birth rate to no avail, a lesson that other countries struggling with falling birthrates might take to heart. The United States has fallen below replacement for the fifth straight year. Singapore’s measures have included annual exhortations of calls to patriotic duty as well as paid maternity leave, childcare subsidies, tax relief and rebates, one-time cash gifts, and grants for companies that implement flexible work arrangements. Current cash incentives to have children include a new so-called Baby Bonus of S$3,000 (US$2,231), which raises the reward to S$11,000 for each of their first two children and up to S$13,000 for each subsequent child. A government spokesperson said the government is now looking at increasing paid parental leave. Despite these efforts, the fertility rate deteriorated from 1.41 in 2001 to its current level. Replacement is 2.1 per woman of child-bearing age.

As part of its package of pronatalist incentives, according to a March 2020 study of Singapore’s plight titled Reversing Demographic Decline by Tan Poh Lin for the International Monetary Fund, the government “subsidizes up to 75 percent of assisted reproductive technology treatment costs for qualifying married couples and allows them to tap into their medical accounts under the national savings program to pay for the procedures.” But access to invitro fertilization and other reproductive technologies “is not sufficient to ensure that older women have enough babies to compensate for fertility decline among younger women.” Japan, the study points out, has the world’s highest percentage of babies born through IVF (about 5 percent), but, like Singapore, has one of the world’s lowest fertility rates. It is not so much an Asian problem as much as it is an urban one.

And the government, despite the success of many of its social engineering campaigns – including, famously outlawing chewing gum – has been learning to its sorrow that it is easier to stop women from having babies than it is to encourage them to, which Singapore also tried, and apparently had more success at doing. Starting in 1966, the Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, in a mistaken belief that rich people, or better-educated ones, would produce higher-quality babies, began to aggressively target low-socioeconomic status individuals, particularly females, to use such as condoms and other forms of birth control, establishing the "Stop-at-Two" program, which encouraged and benefited two-children families, and promoted subsequent sterilization. The government in general discouraged having more than two children. Government workers were denied maternity leave after their second child. They raised the hospital fees for third and subsequent children and entry to the top schools choices were given only to children with parents who had been sterilized before the age of 40. Sterilization earned seven days of paid leave.

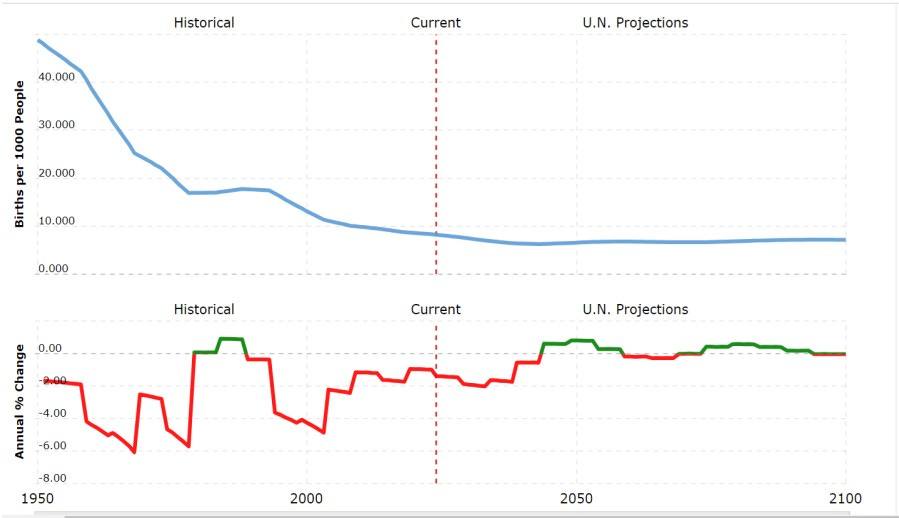

It worked, or more likely increasing urbanization worked. In the 1980s Singapore discovered it had not an overpopulation problem but an underpopulation one. The "Stop-at-Two" campaign ceased and in 1984 the government created the Social Development Unit, or SDU, to promote marriage and romance between educated individuals. That eventually included running a ‘Love Boat,” a free weekend cruise up the coast of Malaysia for couples to mingle as they chose. Mingling appears to have been problematical. Cynics took the SDU acronym to stand for ‘single, desperate and ugly.” Eventually ‘Stop at Two’ was replaced with the "Have-Three-or-More (if you can afford it)" campaign in 1987. As the United Nations projection of Singapore’s birth rate per 100,000 population shows, having three or more is a fanciful goal. While long-distance projections are always more of a guessing game, the UN apparently believes Singapore’s birth rate will never recover. The annual change, as shown in the second graph, has been declining since 1990 and will continue to decline through at least 2050.

“In the case of Singapore, the government has grappled with the relentless downward trend in fertility since the 1980s,” Despite these efforts, Tan wrote, the fertility rate has continued to deteriorate, as it has globally in industrialized countries.

(According to the CIA World Factbook, Nigeria has the highest birth rate in the world at 47.28 average annual births per 1,000 people per year. Data from other sources, such as the United Nations or World Bank, rank countries in a slightly different order, but central Africa is the fastest-growing region globally and Nigeria the fastest-growing population in every case.)

“The majority of (Singaporean) married couples have children, but most stop at one or two, owing to high education-related expenses and the desire to invest more in each child,” Tan wrote. ‘Couples who might otherwise want children voice concern over the ethics of a stressful childhood and upbringing or worry that they would lack the energy or ability to help their children compete effectively. Singapore’s human capital success story, which has propelled it to the top of international rankings, thus comes at a cost to its people’s willingness and ability to build families. The inability to raise the fertility rate is hence not so much a testimony to ineffective pronatalist policies as to the overwhelming success of an economic and social system that heavily rewards achievement and penalizes lack of ambition. Tackling the fertility rate may therefore require confronting some of the weaknesses of the underlying system, which means not only addressing demographic challenges, but also potentially helping build social cohesion or healthy cultural attitudes toward risk taking.”