Transnational Crime Steals Billions in Southeast Asia

New UN report says cyberscams, illegal gaming spreading, overpowering governments

Transnational organized crime in Southeast Asia, driven by sophisticated new technologies including artificial intelligence, stablecoins and blockchain networks, is evolving faster than at any previous point in history and expanding across the globe, fleecing victims on every continent and outpacing the efforts of governments to combat them, according to an explosive new 92-page report released today (April 21) in Bangkok by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

“We are seeing a global expansion of East and Southeast Asian organized crime groups,” said Benedikt Hofmann, UNODC Acting Regional Representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, in a prepared news release. “This reflects both a natural expansion as the industry grows and seeks new ways and places to do business, but also a hedging against future risks should disruption continue and intensify in Southeast Asia.”

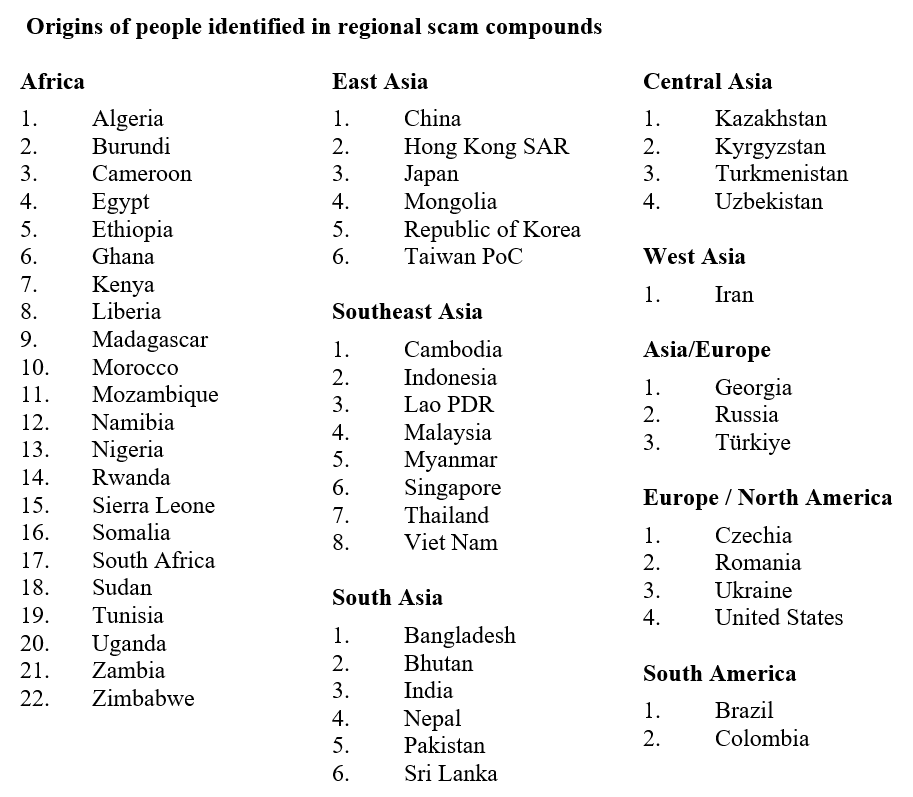

As these criminal networks have grown more sophisticated, they are increasingly taking on the guise of supposedly respectable industrial and science and technology parks as well as casinos and hotels, employing hundreds of thousands of multilingual trafficked victims and complicit individuals, according to the report, rapidly enabling Asian crime syndicates to broaden the scope of fraud victims being targeted globally and exacerbating existing challenges faced by law enforcement.

This transformation, according to the UNODC, under the relatively cumbersome title “Inflection Point: Global Implications of Scam Centres, Underground Banking and Illicit Online Marketplaces in Southeast Asia,” has been marked by proliferating “industrial scale cyber-enabled fraud and scam centers, driven by sophisticated transnational syndicates and interconnected networks of money launderers, human traffickers, data brokers, and a growing number of other specialist service providers and facilitators.”

The victims aren’t just in Southeast Asia. In the US alone, investigators found, more than US$5.6 billion disappeared from victims to cryptocurrency scams in 2023, with an estimated US$4.4 billion of that attributed to so-called ‘pig butchering’ schemes, most prevalent in Southeast Asia. That is a relative pittance compared to losses in East and Southeast Asia, estimated at US$37 billion.

A 13-person core team assembled the report, leaning on help from governments in East and Southeast Asia, international partners and other organizations with the support of research experts of UNODC field offices based in Brazil, Latin America, the Middle East and North America, South Africa, and West Africa, as well as several experts in the field, an indication of how far these organized crime groups have spread their tentacles.

This level of criminal activity has particularly frustrated China, whose leader Xi Jinping has virtually ordered governments in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia, the Philippines and Myanmar to do something about it. The Cambodians attempted to throw Chinese gaming operations out of the resort city of Sihanoukville several years ago, causing tens of thousands of Chinese nationals to decamp.

In 2024, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. ordered dozens of Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, or POGOs to close, with an equal number of Chinese leaving. But months later authorities are still finding the operations scattered around the country. They are fungible and leave quickly for new destinations where law enforcement is weak, and governments are malleable. South Pacific statelets like Vanuatu and the Marshall Islands and others are new targets.

These scam centers, most of them run by a huge criminal diaspora of Chinese gangsters, have been the focus of an extensive series of Asia Sentinel articles over the past two years. The gangs specialize in money laundering related to unregulated casinos and online gambling operations centered in huge compounds “mostly in inaccessible and autonomous territories, Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and other vulnerable border areas across the region, especially in the Mekong, which have served as breeding grounds for criminal networks,” the report notes.

As a result, “Asian crime syndicates have emerged as definitive market leaders in cyber-enabled fraud, money laundering, and underground banking globally, actively enhancing collaboration with other major criminal networks around the world.”

There are as many as a dozen known sites in the border areas of Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia, enslaving hundreds of workers from around the world in huge compounds, lured by the promise of legitimate jobs. These groups have grown rapidly, “demonstrating their ability to adapt to and capitalize on changes in political and business environments, exploit gaps in governance and regulations, and rapidly develop advanced physical and digital infrastructure while integrating new business models and technologies, including malware and artificial intelligence, into their operations.”

These illicit online marketplaces “have dramatically expanded criminal revenue streams and enabled transnational organized crime to scale up operations,” according to the report, “creating new opportunities to expand physical bases of operation overseas and increasingly being used by criminal groups outside of Southeast Asia to launder proceeds of crime and circumvent formal financial systems. “

With overpowered governments intensifying their efforts to close the scam centers, they have responded by hedging both within and beyond the region. “It is now increasingly clear that a potentially irreversible spillover has taken place in Southeast Asia, leaving criminal groups free to pick, choose, and move jurisdictions, operations, and value as needed, with the resulting situation rapidly outpacing the capacity of governments to contain it. More than this, the region has emerged as a key testing ground for organized crime, which is reflected in increasing linkages to criminal ecosystems in other parts of the world facing similar vulnerabilities and challenges. Nigeria, already known as one of the global epicenters of internet scams, is now a new local for the transnational Asian operators.

Amidst heightened awareness and enforcement action taken by governments to address the crisis, Asian crime syndicates have sought to hedge their risk and ensure business continuity by expanding new and existing operations deeper into many of the most remote, vulnerable, and underprepared parts of Southeast Asia, and increasingly other regions. The dispersal of these sophisticated criminal networks within areas of weakest governance has attracted new players, fueled corruption, and enabled the industry to continue to scale, culminating in hundreds of large-scale scam operations conservatively generating tens of billions of dollars in annual profits.

Like any multinational companies, the report says, “transnational criminal enterprises seek out conducive conditions that protect and insulate their businesses and ensure limited government interference. In so doing, major crime groups have converged around and, in many cases, infiltrated venues and businesses including casinos, SEZs, business parks, and various traditional financial and virtual asset services that have proven to offer all of the conditions, infrastructure, and regulatory, legal and fiscal covers required for sustained growth and expansion.”

This approach has proven highly effective, giving rise to a “sprawling, interconnected ecosystem within which organized crime syndicates exploit gaps and vulnerabilities, jeopardize state sovereignty, and distort and corrupt policy-making processes and other government systems.