As Vietnam’s President Visits UN, ‘Carbon Neutrality’ Vanishes at Home

In Vietnam, arrests mean it’s not easy being green

By: David Brown

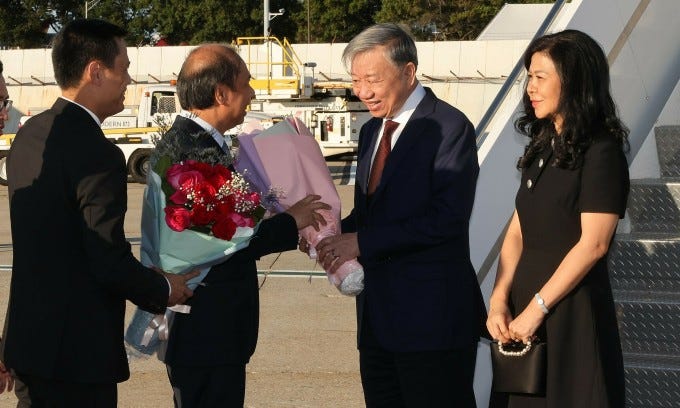

Just a few days after police general Tô Lâm was confirmed as the Vietnamese Communist Party’s new General Secretary, he visited his Chinese counterpart in Beijing where, according to Chinese media, Xi Jinping confirmed the ‘strategic significance’ of the bilateral relationship. This inevitably prompted speculation in Vietnamese media: when would Tô demonstrate Hanoi’s commitment to “balance” in its relations with the Pacific superpowers by visiting the American president?

However auspicious a Biden-Tô meeting might be in the opinion of Vietnam’s public, Tô will at most score only a handshake with Biden while both are in New York for the UN “Summit of the Future” this week. Lâm arrived on September 20 to address both the Future Summit and the General Assembly. Biden will address the General Assembly on September 24. A substantive meeting is pointless until the US has inaugurated a new president.

Obviously, there will be a profound difference in the evolution of the US-Vietnam ties if Donald Trump wins back the White House and erects a trade-stifling tariff wall. Analysis of that possibility can wait until January, if ever. In this story, the focus is on bilateral business as usual.

For starters, it’s important to note that polls consistently show that Vietnam’s citizens are among the most pro-US and anti-Chinese people worldwide. American tourists, even frugal backpackers, are warmly welcomed. That’s misleading. Consistent with the stance of the all-powerful Communist Party, the posture of Vietnam’s government is considerably different. Vietnam’s relations with the US are relations of convenience, not of love. Hanoi needs what the US in particular can supply: technology to produce sophisticated components and ready markets for these and its other products. Its interest in US defense items is restrained and pragmatic (the Russian stuff is cheaper and familiar). More than any time since economic liberalization began a quarter century ago, on matters of discipline the CPV is inflexible; it won’t loosen its grip on decision making or the direction of development.

With this in mind, it’s instructive to consider two extensive and ostensibly cooperative encounters among the US, its allies, and Vietnam.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership Pledge

Eager to capitalize on the promise of broader and freer access to foreign markets, Vietnam in 2018 ratified the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP, the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership quashed by Trump in 2017, and the EU-VN FTA (European Union-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement) in 2021. Both pacts oblige members to allow the formation of free trade unions. To comply, Vietnam’s National Assembly passed a reformed labor code which allows “workers’ representative organizations” to petition employers without interference by Party and state authorities.

However, the legislature hasn’t passed implementing legislation. Instead, and apparently in accordance with “Politburo Directive 24” – a classified document issued in 2023 and leaked in February 2024 – the Ministry of Public Security has rounded up and jailed civil society activists who had presumed to advise the Government on the implementation of Vietnam’s commitment to allow free trade unions.

Only Canada among Vietnam’s Pacific (CPTPP) trade partners has made a fuss. The US has never joined. The European Union – which during the FTA negotiations strongly pressed Vietnam to agree to free trade unions – may yet sanction Vietnam.

The Just Energy Transition Partnership Fiasco

“Hostile and reactionary forces have thoroughly taken advantage of the international integration process to increase their sabotage and internal political transformation activities … forming ‘civil society’ alliances and networks, ‘independent trade unions,’… creating the premise for the formation of domestic political opposition groups,” – Vietnamese Politburo Directive 24, July 2023

At COP26, the 2021 iteration of the global conference on climate change, Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính made a startling announcement: Vietnam would be ‘carbon-neutral’ by 2050. A year later, Vietnamese energy experts and foreign counterparts were deeply engaged in negotiating details of a “Just Energy Transition Plan,” a package of loans and technical assistance valued at US$15.5 billion dollars for the first five years.

At the same time, Vietnam’s energy bureaucrats were laboring to birth Power Development Plan #8. It was already two years behind schedule. The bureaucrats were comfortable with coal, oil and gas, and hydropower, which have been the staples of the nation’s power sector. They were not comfortable with solar power and wind power, new technologies that Vietnam is perfectly suited to exploit. They were annoyed that a gaggle of civil society “new energy” experts were advising not only the JTEP negotiators but also the Prime Minister’s Office.

Again it was the Ministry of Public Security that sorted things out. One by one, police arrested the leaders of four non-profits, people who Ben Swanton of the 88 Project, a human rights advocacy group, describes as “professionals…who didn’t identify with an anti-state ideology, who were playing by the government’s rules, working within the state-sanctioned space for civil society.”

The charges levied against the six environmentalists were neither novel nor plausible – not the usual “spreading anti-state propaganda” nor its like, but, in five cases, “tax evasion,” and in the sixth, “appropriating government documents.”

Although the Western officials who negotiated the JETP with Vietnam could not have believed these accusations, they didn’t protest the arrest of their Vietnamese colleagues, at least not publicly. Evidently, preserving a working relationship with their government counterparts is regarded as the higher priority.

It was a clear win for Vietnam’s energy bureaucrats, who now must prove they can direct a successful transition away from coal. Perhaps they can: This summer a new 500-kilovolt transmission line from central Vietnam to the industrial zones around Hanoi was completed in record time, doubling capacity and allaying foreign enterprises’ fears of another power-starved summer.

David Brown is a former US diplomat with extensive experience in Vietnam and a regular contributor to Asia Sentinel