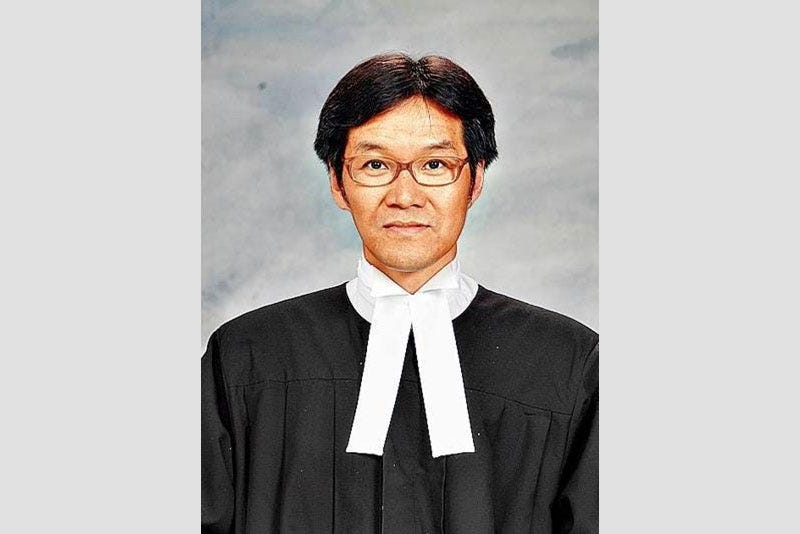

A Wolf in Judge's Robes: The Show Trials of Judge Kwok Wai-Kin (Part 2)

Judge Kwok's brazen politicization of four NSL cases, and the lack of consequences for it, shows how far Hong Kong's judiciary has fallen

The following, though much longer than Asia Sentinel’s normal articles, is reprinted with permission from the “Hong Kong Law & Policy” blog on Substack of Samuel Bickett, formerly an American corporate lawyer who was arrested in 2019 for allegedly interfering with a police officer who refused to identify himself and who was beating a youth who reportedly had jumped a turnstile. Bickett was ultimately sentenced to four months and two weeks in jail. The experience turned him into a human rights lawyer. He is now based in Washington, DC as a legal fellow at the Georgetown Center for Asian Law. This is part 2. You can read Part 1 here.

Last month, I wrote about District Court Judge Kwok Wai Kin’s journey from disgrace and quasi-suspension to appointment as a national security judge. In this article, I delve into his national security rulings since then. My analysis aims to provide a clearer understanding of how Beijing's handpicked national security judges blatantly manipulate the law, evidence, and rights of defendants in national security proceedings. Judge Kwok’s conduct from the bench exposes a system where judges, prosecutors, and police appear to be staging theatrical performances rather than trials, all of which are designed to reach one end: conviction and imprisonment.

As a national security judge, Judge Kwok Wai-Kin has ruled on four cases involving 15 defendants—two for sedition and two for subversion. He has presided over one trial against defendants accused of writing “subversive” children’s books about wolves and sheep, and issued sentences in three cases where the defendants pled guilty (a common occurrence in a system where few hold any hope of a fair trial). Kwok sentenced all 15 defendants to prison or juvenile detention.

Kwok is currently overseeing the sedition trial against Stand News and its former editors-in-chief. In the coming weeks, he is expected to issue a verdict and sentence, and there is little doubt as to the outcome.

Judge Kwok’s behavior is are not unique; it increasingly represents the norm for Hong Kong’s courts. However, unlike some of his peers, Judge Kwok seems especially unable to conceal his personal opinions and biases. This trait led to his prior suspension in 2020 and makes him an ideal subject for examining the infiltration of extremist anti-liberal views within Hong Kong’s judiciary.

Judge Kwok is best known for his political statements from the bench, which often have little bearing on the case at hand. Beyond that, however, he uses a variety of methods to manipulate facts, law, and court procedure to disadvantage defendants. Several common themes that appear in his judgments:

Implying violent intent without evidence: Hong Kong’s national security cases have rarely involved violence, but Judge Kwok often infers violent intent from nonviolent acts. In two separate instances, he determined that the defendants must have had violent intent because their political goals were opposed by Beijing; In Kwok’s mind, the only way to achieve such goals would be through violence, not persuasion.

Misuse of the rules of evidence: In several cases, Judge Kwok has misused an evidence principle called “judicial notice” to draw conclusions without any evidence. He has also repeatedly allowed the prosecution to use evidence never provided to the defense.

Ignoring laws and evidence to issue harsher sentences: At sentencing, Kwok consistently exaggerates the defendants’ actions to increase sentence lengths and dismiss mitigating factors. In one particularly flagrant instance, Kwok imposed a mandatory minimum sentence despite determining that it was not actually mandatory, effectively changing the charged crime to a different crime.

While Judge Kwok may be especially inept at covering his tracks, other judges have employed these same tactics. For example, many of these same tactics were used in my own case, and they’re being used now in the ongoing Hong Kong 47 trial.

Kwok’s mishandling of the Union of Speech Therapists’ trial

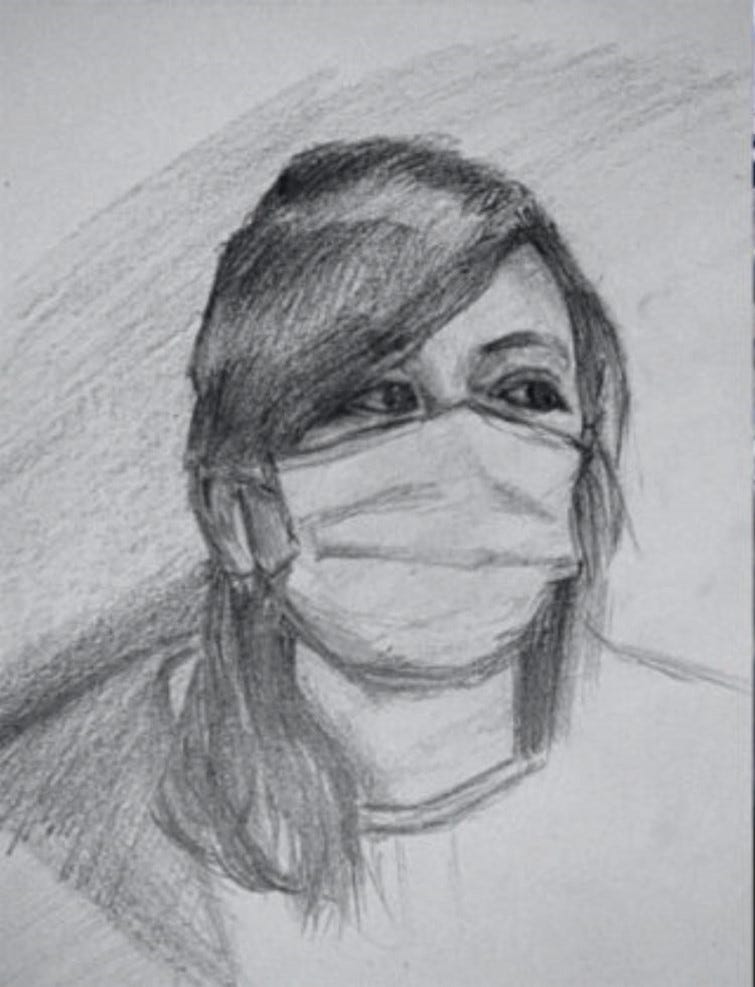

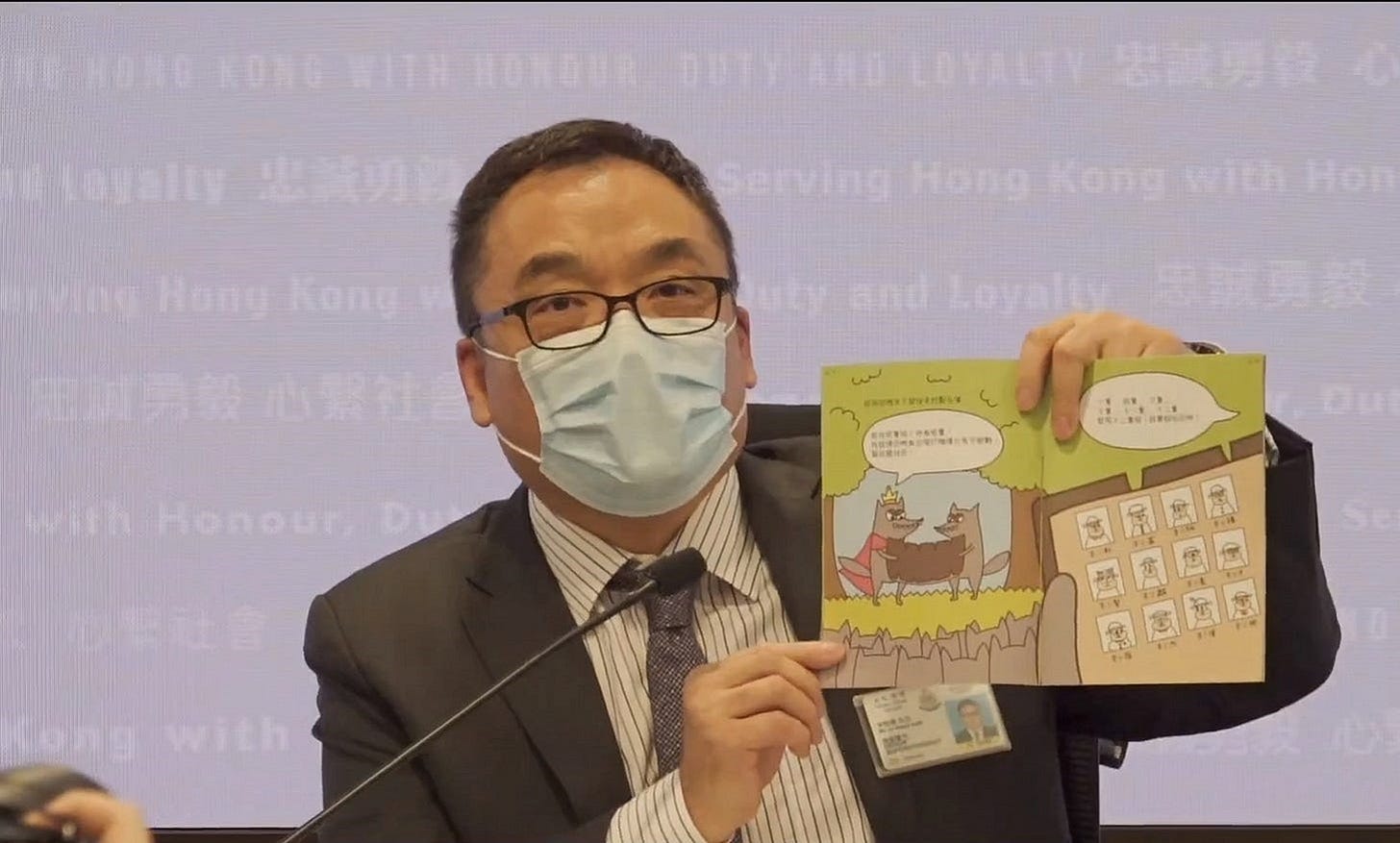

Judge Kwok’s most high-profile national security case (other than the still-unfinished Stand News trial) was a sedition trial against five members of the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists. They were accused of bringing “hatred and contempt” upon the government by publishing a series of children’s picture books featuring wolves (said to represent the Hong Kong Police) and sheep (said to represent the Hong Kong people). The case gained significant attention both locally and internationally.

In Hong Kong, the colonial sedition offense controversially does not require violence, criminalizing any act, speech or publication that brings “hatred or contempt” upon the government, “raises discontent or disaffection” among the public, or “promotes feelings of ill-will and enmity” between different classes of the population. It is an extraordinarily broad and vague statute, designed that way by a colonial British administration that at the time was seeking leverage to repress political dissent. It fell into disuse after Britain’s liberalization in the latter portion of the 20th Century, but has been revived since the 2019 protests by another distant power ruling the city: Beijing.

The sedition law is plainly incompatible with the Basic Law and Hong Kong’s international treaty obligations, which guarantee free speech. But that hasn’t stopped Hong Kong’s courts from going along with the government’s efforts. After a five-day trial, Judge Kwok convicted all five defendants.

Throughout the trial, Kwok’s blatant manipulations of law and evidence, as well as his politicized statements, raised eyebrows.

In his reasons for verdict, Kwok agreed with the defense that the children’s books were “just a fable teaching some universally celebrated values,” as they do not actually categorize the sheep or wolves as real members of society. Nonetheless, he declared that the “biggest problem” with the books “is that after the story is told, the children are to be told that the story is real. They will be told that in fact, they are the sheep, and the wolves who are trying to harm them are the PRC Government and the Hong Kong Government.” In other words, these defendants were guilty of sedition not because of the contents of their books, but because of what other people might say about them.

In addressing the facts, Kwok also blatantly misused a legal principle called “judicial notice” in order to draw conclusions without the evidence to back them up. Normally in trials, every fact must be supported by evidence. Lawyers can’t simply argue whatever they want; they have to present documents, videos, witness testimony, or some other evidence that supports every assertion.

But judicial notice is an exception to this rule. It allows a judge or jury to use a fact of "general knowledge” without evidence being introduced, but only if it is common sense and indisputable.

Judicial notice is used frequently, but the rule is extremely narrow. One common example of its use is for dates: that the handover of Hong Kong from London to Beijing occurred on July 1, 1997, for example, is a general fact that is indisputable, and if it becomes relevant to a case, the parties don’t need to provide evidence to support it.

In contrast, disputed facts about political events would never be suitable for judicial notice. “There were political demonstrations in Hong Kong in 2019” could probably be taken as judicially noticed, but “The gathering at the Legislative Council on June 12, 2019 was a riot” could not, because that is a disputed assertion.

Yet, Judge Kwok decided to take judicial notice of a long list of controversial facts. He characterized the 2019 assemblies as “unlawful.” He accused protesters of displaying “street propaganda, cyber abusing, doxing,…vandalism, vigilantism, criminal damage, paralyzing public transports, etc.” He claimed that LegCo had been “besieged by protesters.” He specifically described two incidents on October 1 and 4, 2019, as “riots.” At the same time, he made no mention of the widespread violence by police or violence by Beijing’s supporters against protesters, despite Kwok himself having presided over one such case involving a man stabbing three protesters (see Part 1 of this series).

To use judicial notice for these highly controversial facts was plainly an abuse of the principle. It allowed Kwok to conclude that the assertions about police and government misconduct implied by the “wolves” in the children’s books were false, without having to prove it. In doing so, he bypassed the most fundamental rule of criminal trial procedure: that the prosecution must prove its charges with evidence.

The problems with Kwok’s decision didn’t stop there. Further along in the Reasons for Verdict, Kwok launched into a political rant about the protest movement. He claimed, without evidence, that “it can be said with certainty that there were over tens of thousands” of Hongkongers who had participated in “riotous activities.” He then claimed that “these people” did not “recognize the sovereignty” of Beijing over Hong Kong, despite that calls for independence were rare during the protests, and said that the protesters “did not support the policy of ‘One Country, Two Systems.’” All of this, to Kwok, indicated that there was “a strong pressing need to safeguard national security in HKSAR to prevent riots and civil unrests of any magnitude from happening again.”

Kwok’s politicized statements in announcing the verdict raised eyebrows, but turned out to just be a warm-up. Three days later, court reconvened for mitigation and sentencing.

Often in these rigged political cases, the mitigation speech is the only real opportunity for defendants to make a defense of their principles—to the public if not the court. For a defendant to issue their own mitigation speech, they have to first dismiss their lawyers and appear unrepresented. Two of the five defendants, Melody Yeung and Lorie Lai, decided to do just that.

Yeung was up first. “Rather than a trial on the seditious behavior of the five people in front of the court to ‘spread rumors,” she began, “it is more of a trial on the correct view of history.” She compared the proceedings to Rome putting Galileo on trial for saying the earth revolved around the sun, or Athens putting Socrates on trial for his views on philosophy. “Only the public can put the three picture books on trial as to whether they sincerely reflect the social relations in Hong Kong,” she continued.

But in the middle of her speech, Judge Kwok interrupted her. He warned her that her speech was “drifting into matters of a political nature.” There were disbelieving mumbles in the audience, most of whom had heard Kwok just days before give a political speech of his own.

Yeung then quoted Martin Luther King, Jr.: “A riot is the language of the unheard.” She placed herself and her co-defendants in the context of “countless rebels who were imprisoned, tortured or executed in the name of the law.” She continued:

“This is the moral obligation we take on. This is the intention of publishing the picture books—to point out that the behavior of the sheep in the story is legitimate. Rather than inciting to so-called violence or hatred, direct or indirect, the picture books are preventing violence—structural violence.”

Then, Kwok interrupted her again, warning her not to cross the “political” line. Yeung persisted. She concluded the speech by courageously doubling down on her principles:

“I don’t regret my choice and hope to stand for the sheep from beginning to end. My only regret is in not publishing more picture books before my arrest, and not being insistent enough on the quality of the books.”

The second defendant, Lorie Lai, then stood up and began her speech:

“This trial is all about one question: How free is freedom of speech? Meaning, is there any boundary of freedom? Do we have to bear any cost? Is limited free speech really free? The prosecution cited extreme examples of terrorists to justify its limits…”

Quickly, Kwok interrupted her, this time more forcefully. He objected that her speech amounted to a “political declaration” and that he wouldn’t allow it.

Barred from giving the only speech she wanted to give—her only chance to present her viewpoint—she sat down. (Later, she released the full speech.)

In his later Reasons for Sentence, Kwok explained his decision, saying that Lai’s “address was political in nature that could not be allowed.”

These speeches were directly relevant to the issues in the case—this was, after all, a case about political publications and their intent. Yet, it was Kwok’s subsequent hypocrisy that really underscored how outrageous his interruptions had been. Just after the mitigation speeches had been halted, Kwok himself then launched into another of his famous political tirades. I reprint it in full below (paragraphs 36-39 in the written version), as it’s really worth reading to understand how exceptionally unhinged it was, having nothing to do with the legal issue before him:

“Defendants, you are going to leave custody soon, but my question to you is: when are you going to leave the prison of your mind? You or some of you have said that the picture books were intended to be true records of the events so that the facts would not be lost, and that facts had to be preserved to prevent ‘brainwashing’ of children by the authorities through the anticipated patriotic education in school. However, may I respectfully ask all of you to think, if you have not yet done so, the following.

“Have you really put the true record of events in your picture books? There is no doubt that the sheep village in the books refers to Hong Kong, and the wolves’ village refers to PRC. It does not require this court to make the finding by drawing inferences from evidence because you have said so in the Timeline page in Book 1. If so, have you really put the truth before the children? Can you explain why you didn’t tell the children that the sheep village (ie Hong Kong) was in fact part of the land owned by the wolves (ie PRC), and that the land was taken away from the wolves through military invasion of PRC on the part of the shepherd? Why didn’t you tell the children in the book the reason for which the shepherd left the village? Why didn’t you tell the children that the shepherd had to return the sheep village to the wolves because they had no right whatsoever to keep it any longer? Were you really honest when you brushed the true reason under the carpet and hid it from the children by simply telling them ‘one day, the shepherd suddenly left’ as in page 7 of Book 1 so that you could avoid telling the children that PRC was getting back what should never have been taken away from her in the first place? Was it that you could not tell the children the truth in this respect, or else you would not have any moral high ground to tell your story further to the children, and/or you would not be able to instill the fear and hatred in the minds of the children against PRC?

“Furthermore, when you said that you did not want the authorities to “brainwash the children”, then why is it that you had the right to brainwash them? According to the evidence, one of you had said that children were like white sheet, and you people had to act first. Of course, you may argue that education is a kind of brainwashing anyway, but if that is your justification, as a teacher, why didn’t you put all the fundamental facts before the children but hid from them? In Europe, no one can in the exercise of his freedom of speech deny the existence of Holocaust, then why is it that you would have the right, in HKSAR, to deny that PRC has undisputable sovereignty over HKSAR which is an alienable part of the PRC, and instill this kind of ideas into the mind of children who should be taught to love his country and his homeland?

“Of course, I am nobody to teach you. But if you stick to the same thinking that motivated all of you to publish the books, you are just locking yourself up in a prison of your mind. You cannot deny the relationship between PRC and HKSAR. This is the legal position. This is the internationally-accepted position. It is the historical position. It is also morally wrong for you to say that Hong Kong and PRC are separate, no matter how you perceive the PRC, the Central Authorities and the Government of HKSAR. For instance, if you have a bad impression of another person, such as a thief, and you have no doubt that your impression represents the truth, does that give you a right to take away his property? As I have said, I am nobody to teach you. As counsel has said, you are elites of the elites. You are smart persons, and you can make up your mind. I have sidetracked enough, and shall return to the sentence.”

Having just blocked a defendant from exercising her right to speak in her own defense for being too “political,” Kwok delivered what sounded more like a radical politician’s stump speech than a judge delivering a sentence.

Kwok’s speech was indisputably inappropriate for a judge. Media spread the incident widely, but the outrage was relatively muted compared to the reaction to Kwok’s misbehavior in 2020. In the public’s mind, a judge launching into a political tirade no longer threatened the credibility of the judiciary, because the judiciary had no credibility left.

The pamphleteers

In three other national security cases overseen by Judge Kwok, the defendants have pled guilty in hopes of at least obtaining a sentence reduction. The first of these occurred in January 2022, in which Kwok sentenced a teenage boy and an adult woman who had pled guilty to sedition. Their crime was non-violent, involving the placing of a handful of amateurish pamphlets around the city supporting republicanism and establishment of a Hong Kong militia. Other than placing a few documents around the city, there was no evidence of the defendants taking any action to further their political goals.

Even in the straightforward matter of issuing a sentence, Kwok’s ruling was rife with legal problems. Kwok sent the teen to a rehabilitation center (juvenile detention for an indeterminate period), and imprisoned the woman for 13.5 months. Before issuing the sentence, Kwok once again took judicial notice that “social disorders and riots had frequently occurred prior to the enactment of the NSL, but after the NSL had come into effect at 11 p.m. on 30 June 2020, such social disorders and riots were suppressed.” This was another abuse of the judicial notice mechanism, as Kwok’s conclusion was not just disputable but objectively wrong: the Covid-19 pandemic, combined with cold weather and a sense of fatigue, had ended the protests months before the NSL came into effect.

Kwok also misapplied the sedition law itself. The sedition statute, Section 9 of the Crimes Ordinance, is a repressive law, but it explicitly exempts speech that advocates for changes in Hong Kong law. Yet Kwok didn’t even mention the statute’s protections of this sort of speech. Instead, he claimed that calling for a republican form of government and a Hong Kong militia must be calls for violent rebellion—not because the defendants actually called for any such violence, but because Beijing “will never permit such changes to occur.” In other words, Kwok’s position was that Hongkongers can only advocate for changes to the law if they are already supported by the government; anything else is seditious.

At the hearing, the defendants’ counsel showed, through case precedents, that the normal penalty for sedition in common law countries, including Hong Kong, is a fine with a suspended sentence. But Kwok, seemingly determined to imprison the defendants, rejected these precedents. Instead, he referred to a small set of cases stemming from the 1967 anti-colonial unrest in the city, a period in which dozens were killed by the violence. Invoking those cases in a nonviolent case of pamphleteering makes no legal sense, but Kwok used these cases to justify prison sentences for the two defendants.

Throughout this case, Kwok advocated for a broad and aggressive reading of the sedition statute. For a judge who has often claimed that Beijing is not a colonial power, it is ironic that he has become such a champion of a law that has long been identified with colonial repression in Hong Kong.

Student Politicism

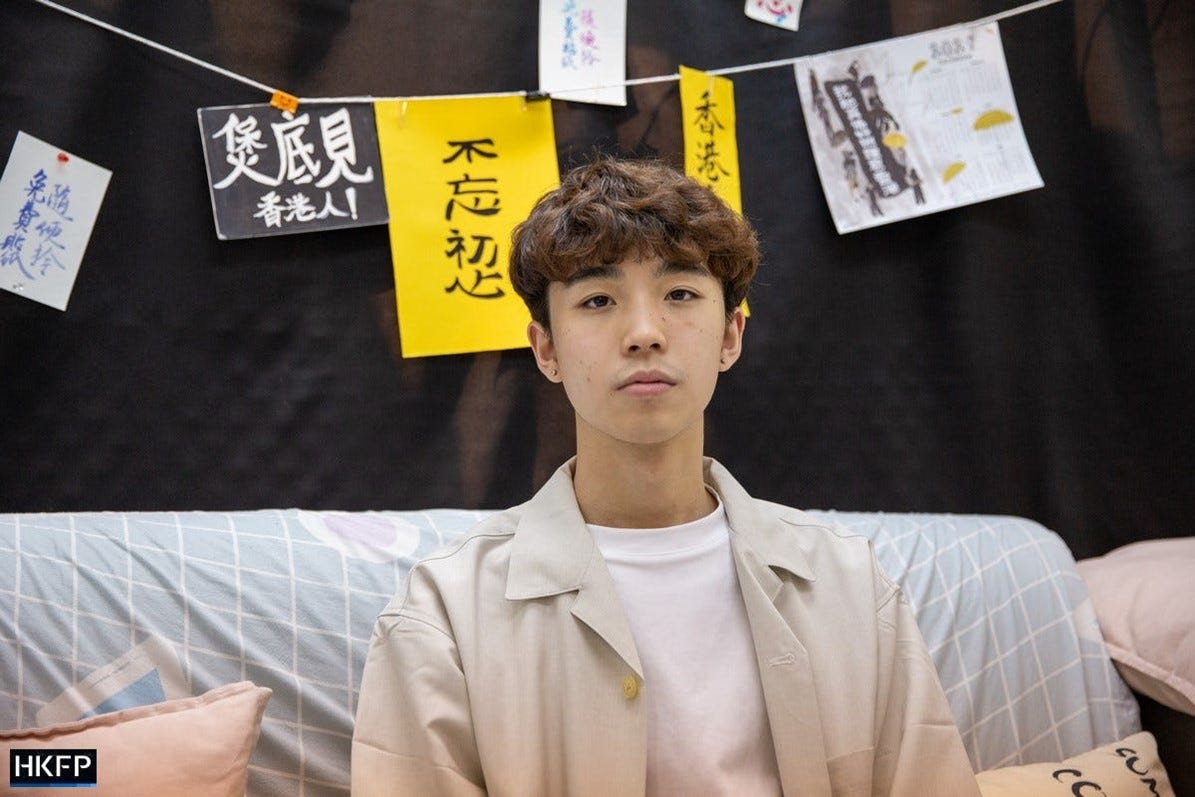

Judge Kwok’s next national security case was a conspiracy to commit subversion case against four leaders of Student Politicism, which he handled in October 2022. Student Politicism was an activist group that set up several street booths in 2020 and 2021 calling for democracy and the development of Hong Kong’s distinct cultural identity.

All four defendants pleaded guilty. After holding a mitigation hearing in which defense counsel argued for reduced sentences, Judge Kwok sentenced the three adults to between 30 and 36 months in prison, and Alice Wong, a minor, to juvenile detention of up to three years in a “training center.”

At the mitigation hearing, Kwok grasped for ways to increase the length of the sentences. He rejected a sentence reduction for the group’s convenor, 21-year-old Wong Yat Chin, because, Kwok said, a recent Facebook post from Wong “called for action.” The supposedly dangerous action Wong has called for was telling people to “breathe well, think well, and live well.”

Kwok reconvened the case a month later and issued his Reasons For Sentence, in which Kwok turned to his usual mix of gaslighting and political lecturing. In particular, he argued that the crimes were “very serious” because the defendants “believe that power should belong to the ‘Hong Kong people’ or what they call the ‘Hong Kong ethnicity,’” but “since ancient times, Hong Kong has been a part of China, and the Hong Kong people belong to the Chinese ethnicity.” As with previous cases, Kwok twisted a political position—in this case, that Hongkongers should be treated as a distinct and autonomous people from Mainland Chinese—and declared it to be subversive for little reason except that he disagreed with it.

At mitigation, defense counsel noted that the defendants had never called for separatism or revolution, but rather had been arguing for changes in government policy. At sentencing, Kwok rejected this. In support, he cited a number of the defendants’ actions that he said amounted to calls for “separatism,” including:

Wong claimed that China was causing Hong Kong’s “cultural erosion” through pressure to adopt Mandarin language and culture. Kwok said this was separatist because Wong intended it to “create panic.”

Kwok said that remembering and supporting the Hong Kong 12—a group of protesters who had been caught fleeing to Taiwan—was separatist. “They used the topic of remembering [the Hong Kong 12] in order to try to make people believe that these 12 Hong Kong people are victims of government suppression rather than fugitives who escaped criminal justice,” Kwok said.

Perhaps most absurdly of all, Kwok said that the defendants were separatists because they “ignored the need for pandemic prevention.”

Student Politicism also promoted healthy living and self-discipline, including recommending that Hongkongers learn martial arts to promote self-control and health. Kwok twisted this to allege that by encouraging people to learn martial arts, the defendants must have been planning to fight a war against China.

If Kwok thinks martial arts can defeat the People’s Liberation Army, he may have been watching too many Kung Fu movies.

Returning Valiant

In his most recently concluded case, Kwok presided over sentencing of members of the localist youth group Returning Valiant. All seven defendants pled guilty to conspiracy to incite subversion, and Kwok sentenced them in two separate hearings. In the first ruling, issued in October 2022 just days before the Student Politicism sentences, he sentenced five teenage defendants to detention of up to three years in a training center. In February 2023, he sentenced two adults to five years’ imprisonment.

The prosecution alleged that the defendants operated street booths and distributed materials calling on others to prepare themselves for resistance. They were never accused of actually committing any violence, purchasing or searching for guns or other weapons, or otherwise taking any act beyond words. Nor was there any evidence that they had actually incited anyone to adopt their ideas. To the contrary, the defendants had consistently stated that “this is not the time for revolution.”

Nonetheless, in sentencing, Kwok declared that their acts were a “serious” conspiracy. Among the outlandish reasons Kwok cited for this finding:

Some of the defendants had toy guns at their apartments.

The defendants could have persuaded others to become violent, even though—as Kwok admitted—no such evidence had been presented.

That the defendants had declared that “this is not the time for revolution” actually increases the seriousness of the offense, as it “shows that they will continue to incite.”

The defendants’ supposedly violent plan was to tell others to “strengthen the mind and practice martial arts.”

The people of Hong Kong would have been receptive to invitations to secession because they “still boo the [PRC’s] national anthem at international football matches.”

Plainly, Judge Kwok was determined to find that the case involved a “serious” conspiracy. But why?

The National Security Law (NSL) provides for a five-year minimum sentence for “serious” subversion cases, so if this were a straight subversion case, Kwok could have used the finding to increase the sentence. But this was a conspiracy to incite subversion case. Conspiracy cases fall under the locally-enacted Crimes Ordinance, not the NSL. As such, the NSL’s mandatory minimum sentence for “serious” cases does not apply.

Kwok admitted that the defendants were not subject to the mandatory minimum. But he then offered a lengthy, nonsensical argument as to why he had the option to apply the mandatory minimums. And that’s exactly what he did.

Hong Kong defendants sentenced to more than a month in prison are virtually always granted a 1/3 sentence deduction for pleading guilty at the earliest stage of proceedings. In this case, the sentencing starting point of six years and 5.5 years for the two adult defendants would have resulted in 4 years’ and 3.6 years’ imprisonment, respectively.

But Kwok denied them this discount—not because he had to, not because it was provided by law, but simply because he felt like it.

Kwok claimed that breaking with this fundamental principle of Hong Kong law was justified because the prosecution could have charged the defendants with subversion under the NSL. But the prosecution didn’t charge them with subversion; if they had done so, they would have had to provide more evidence to establish guilt. The defendants pled guilty to conspiracy, but might not have pled guilty to subversion.

It’s hard to overstate how deeply damaging to rule of law this decision was. Kwok sentenced these defendants based on a crime with which they hadn’t even been charged.

And so it continues…

Since last October, Judge Kwok has been overseeing the high-profile sedition trial against former Stand News editors-in-chief Chung Pui-Kuen and Patrick Lam. Chung testified for a grueling 36 days, in which he exposed the prosecutor, Laura Ng, as an ideologue and eloquently defended the media’s right to publish dissenting views. Closing arguments are set for June.

In any normal court, expectations for an acquittal would be high. But this is not a normal court—it is Kwok Wai-Kin’s court. Under Kwok, a conviction and substantial prison sentence are virtually certain.

Throughout the trial, the prosecution has produce reams of evidence that it never provided to the defense before trial—misconduct that would be grounds for halting the proceedings in normal circumstances. Kwok not only declined to halt the trial, but actually then allowed the prosecution to use the materials against Chung and Lam.

For any who still doubted how the trial would end, Chung’s final day of testimony should have laid those doubts to rest. As Prosecutor Ng completed her questioning, Judge Kwok jumped in with some questions of his own. Kwok quoted a Stand News commentary from journalist Allan Au, which had never been introduced into evidence by either party—another misuse of evidence rules. He then suggested that the 17 opinion pieces that made up the key evidence in the case were “fake news” rather than opinion pieces. Chung, of course, rejected Kwok’s characterization—but that will have little impact on the conviction Kwok inevitably issues.

But it’s not just Judge Kwok that is dismantling the system of free and fair trials. Yes, Kwok is easy to call out, but that’s because seemingly lacks the cleverness and self-control to couch his violations of law in the understated, procedural language of the courts. Many other judges are just as extreme, and just as willing to ignore law and facts in order to reach a conviction. They’re just better, in most cases, at masking it.

Hong Kong’s security minister, the cartoonishly villainous Chris Tang, recently hailed the “100% conviction rate” in national security cases. A 100% conviction rate, of course, is not the sign of a healthy system that Chris Tang thinks it is. But it underscores the real goal here: to the Hong Kong government and its handpicked national security judges, the national security law is supposed to make the courts irrelevant. These judges are not supposed to question the government’s position; they are supposed to implement it.

Judge Kwok and his fellow members of the bench are civil servants in an authoritarian system, nothing more. They are not an independent check on the system; they are functionaries who implement Beijing’s will. The media, and the world, ought to stop treating them like anything else.